Brief thoughts on women writers being erased from SFF – again

Another day, another article* supposedly assessing the cutting edge of Science Fiction written over the decades. Citing twenty five authors. All men. No, I’m not going to link. You can find it for yourself at SF Signal if you really want to. Or whatever particular piece has prompted me to repost this.

Like every other such article, it hands women writers a poisonous choice. We can object, with all the hassles and loss of our own working time which that will entail, as the usual counter-objections come straight back at us. That’s best case. Worst case? The full gamut of ugly insults and threats.

Or we can let the erasure stand, damaging women in SF&F, present and future.

Either way, we lose out.

I can easily predict the ways an objection to this particular piece will be dismissed. “It’s taking the long view and since men have dominated historically, the list will inevitably skew male. There’s nothing to be done about that.”

Yes, there is. Research. Start with Octavia Butler – and while you’re there, make a note that erasing writers of colour and those of differing sexuality is equally damaging and yes, just as dishonest.

Then there will be the expressions of concern – some even genuinely meant. “It’s just one article. Does it really matter?”

No, it isn’t just one article. Stuff like this crosses my radar if not weekly, at least once a fortnight. And that’s without me making any effort to find it.

As an epic fantasy writer, I’m just waiting for the first instance of that now well-established harbinger of Spring. The article saying “Game of Thrones will be back on the telly soon. Here’s a list of other authors you might like (who just happen to all be men).”

And if I object to those? “Oh, don’t take it so personally.”

No, women SFF writers don’t take these best-of lists, these recommended-for-award-nominations and shortlists, these articles and review columns erasing us ‘personally’.

We object because they damage us all professionally.

More than that, erasing women authors impoverishes SF&Fantasy for everyone by limiting readers’ awareness and choices today and by discouraging potential future writers

Which is why this matters.

Every

Single

Time

Right, I have work to do, so I will go and do that. If you want read further thoughts on all this, check out Equality in SF&F – Collected Writing

*I did start adding the dates and reasons every time I reposted this but I’ve had to stop as the list was pushing the actual article off the bottom of the screen… which tells its own tale really.

The importance of thinking about ‘local values’ when you’re writing.

An American pal and her sister spent a few days here recently. A circuitous route to avoid some roadworks took us past Oxford Airport. Or, as I remarked, what locals still call Kidlington Airfield. I mean, the aircraft using it are twelve or twenty seaters.

‘Oh,’ says my pal, ‘big planes then.’ There was a ‘beg pardon?’ pause from me and a laugh from the car’s back seat. You see, these friends grew up in rural Alaska. As far as they’re concerned, a small plane is one where it’s just you and the pilot. Twelve seats? Luxury travel! Because normal is what you grow up with. As you can imagine, that led to a very interesting conversation.

And as is the way with authors, it’s started me thinking about the issues around local values when it comes to descriptive writing. I recall a conversation some time after Northern Storm was first published. In a bar, so after I’d given either a university or local SFF society talk. In that particular book, the magewoman Velindre spends time both in Einarinn’s frozen northlands, and later, in the tropical Aldabreshin Archipelago. The former is ‘bitterly cold’ and the latter is ‘oppressively hot’. I don’t recall what started the conversation but we were discussing exactly what those terms meant to us personally – and why I, as the writer, hadn’t included specific details to make it clear what a thermometer would say.

The first and most obvious answer is because I didn’t need to. With regard to ‘bitterly cold,’ the reader needs to know there’s snow on the ground and water is frozen. There was no plot or character related reason for me to indicate whether the temperature was minus three degrees or minus thirteen. Even a short paragraph going into more detail would have been wasted words and as far as I am concerned, every word in a book must count.

But it goes beyond that. My personal assessment of ‘bitterly cold’ is going to be very different to my Alaskan friend’s. Just as ‘oppressively hot’ means something entirely different to an author friend who lives in Hawai’i. At World Fantasy Con in San Diego a few years back, she was sitting in the full sunshine in a cardigan and considering getting a jacket while those of us just in from a UK October were grabbing all the shade we could find, sweltering in the most lightweight clothing we owned.

So going back to Northern Storm, adding more precise detail to either of those descriptions could well have been actively counterproductive. Specifying ‘oppressively hot’ in my own personal terms could very easily throw a reader used to a different climate right out of the story. Because their instinctive reaction would be ‘Wait, what? No, that’s not hot weather!’ And even something as apparently trivial as that could undermine the whole book for them. Because if a reader can’t believe in the background detail, how are they going to believe in the wizards and dragons?

On the other hand, you can turn this issue of local values to your writerly advantage, in the right place, for the right character. When I said minus three degrees or minus thirteen a few paragraphs back, I meant Celsius, because my local weather values are centigrade. When I come across temperatures given in Farenheit in US crime fiction, I always have to pause and do a quick mental conversion calculation. It disrupts the flow of my reading, so as far as I am concerned, that’s a bad thing.

But if I was a character in a book? If the author wanted to convey someone feeling unsettled and out of their usual place? Sure, that author could tell us ‘She felt unsettled by the unfamiliar numbers in the weather forecast’ but you could do so much more, and far more subtly, as a writer by showing the character’s incomprehension, having her look up how to do the conversion online, maybe being surprised by the result. It gets how cold in Minnesota in the winter?

It doesn’t just have to be about the weather. How about food? Anyone in the UK who travels to different cities and eats in Indian restaurants will know how much the chilli scale on menus varies. As I can attest from personal experience, what’s ‘medium hot’ in Bradford is a world away from ‘medium hot’ in Blandford Forum. There’s a lot a writer can do with that sort of thing.

It’s also worth checking your own local values/understanding against any historical or other background facts and resources you may be using. I was once attending a convention panel discussing the ancient world, when a genuinely baffled audience member sought clarification after a speaker discussed issues arising from the impossibility of telling slaves from free citizens in ancient Athens. But surely, the colour of their skin…? Because that questioner’s knowledge of slavery was entirely US-based and she was assuming central aspects of that were historically universal. Not so, by any means.

That’s perhaps an extreme example, but for instance, I’ve been caught out – though thankfully in a book’s planning phase, not in print – when assumptions I’ve made about growing and harvest seasons, based on my experience living in the UK, turned out to be nonsensical for the different climate and latitudes where I was setting some action.

So it really is worth taking a little time to consider what that well-known online phrase ‘Your Mileage May Vary’ could mean in relation to your writing, for readers and for characters.

Under pressure, I read Pratchett. What’s your refuge reading?

It’s been a bit of a week. Not directly for me and mine – we’re all fine and well, and believe me, I am profoundly grateful. Because around us, folk whom I like and value are having a hell of a time.

Earlier this week I went to the funeral of a local writerly friend, whose unforeseen, terminal cancer diagnosis in January was followed with shocking swiftness by her death. Meantime, another pal who lives hundreds of miles away has been coping with a parent’s emergency hospitalisation while said parent was on a trip to Oxford. So we’ve been offering what support we can by way of local knowledge and resources.

In between times, in bits of down time, I’ve been re-reading Night Watch, and have just picked up The Fifth Elephant. Not for the first time, I’ve noted that the Discworld is where I head these days when I need to press ‘pause’ on things going on around me, to regroup before I re-enter the fray. Not exclusively; glancing along the bookshelves, I note the Kate Brannigan, and the Lindsey Gordon books by Val McDermid also fall into this category of ‘refuge reading’, along with the Elvis Cole novels by Robert Crais. This is by no means the only time I reread these books, and I reread plenty of others. But when the going gets tough? These are the particular books I head for.

I’ve noticed something else recently. While I’ve always had these refuge reads, they’ve varied through the decades and through the different phases of my life. When I was a student, I’d reach for P.G. Wodehouse, Dorothy L Sayers or Dick Francis. When the kids were small, it was Georgette Heyer, Ellis Peters’ Brother Cadfael stories or the ‘Fairacre’ books by ‘Miss Read’. All of which I’ve reread since, but not in quite the same way.

So over to you. Where do you go when you need to find a breathing space, some respite, between the covers of a book?

Guest Post – Jacey Bedford on whether she writes SF or F?

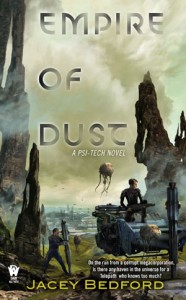

As I’ve mentioned previously, I’m very much enjoying Jacey Bedford’s Psi-Tech novels, namely Empire of Dust and Crossways, which are thoroughly good space-opera ticking all the boxes that first made me love SF while also thoroughly satisfying to me as a contemporary reader. So I was both startled and intrigued to learn that her new book, Winterwood, is a historical fantasy, set around 1800, with pirates and spies and mysterious otherworldly creatures all entangling Rossalinde Sumner in their machinations. You won’t be surprised to learn I invited Jacey to tell us all about that, and she has generously obliged.

SF or F? Trying to work out the differences and similarities.

With Winterwood, the first book of the Rowankind Series, on the brink of publication, Juliet asked me to write about transitioning between writing science fiction and fantasy. I sat down to think about it, but the more I worked on the differences between the two, the more similarities I came up with.

For starters, from the outside it does look as if I made a switch in genres, but it’s not quite the way it looks from the inside. My first two books to be published. Empire of Dust (2014) and Crossways (2015), are science fiction/space opera, but it’s a quirk of the publishing industry that they came out first. Winterwood, my historical fantasy, was actually the first book I sold to DAW, back in 2013, but it was part of a three book deal. DAW’s publishing schedule was such that there was a gap in the science fiction schedule before the fantasy one, so Empire of Dust ended up being published first. The order of writing, however, was Empire, Winterwood, and Crossways.

Confused? I don’t blame you.

Confused? I don’t blame you.

Let me backtrack. The road to publication is often slow and tortuous. Many of us who eventually make it have a drawer full of completed books before getting the magic offer from a publisher. These aren’t necessarily bad books or rejected ones, but ones that have not been on the right editor’s desk at the right time. The difference between a published writer and an unpublished one is often, simply, that the unpublished one gave up too soon. I started writing my first novel in the 1990s without any hope of finding a publisher, and with no knowledge of how to go about it, even if I’d been brave enough to try. That, however, was all about to change – mostly because of the internet. Once I got online in the mid 90s I connected with real writers via a usenet newsgroup called misc.writing, and learned all the basics about manuscript format and submission processes. (And yes, I’m still in touch with some of those very generous writers two decades later.) While all this was going on I finished a couple of novels and made my first short story sale.

The two early novels, at first glance, were second world fantasies, but the deeper I got into them the more I realised that they were actually set on a lost colony world. There are places where science fiction and fantasy cross over to such a degree that it’s hard to see where the boundary is. My lost colony world had telepathy but no magic. So thinking about it logically, how did that colony come to be lost? What put telepathic humans on to a planet and then kept them there, isolated from, and ignorant of, their origins?

That was the question that I started writing Empire of Dust to answer (though it may take all three Psi-Tech books to do it). Because the story involved planets, colonies and space-travel, I was suddenly writing science fiction. I don’t write hard, ideas-based SF. I’ve always been far more interested in how my characters’ minds work than what drives their rocketships, though I’ll always try to make the science sound plausible if I can.

Characterisation – that’s always the crux of the matter for me. Take interesting characters and put them into difficult situations and see what they do. It doesn’t actually matter whether they are in the past or the future, or even on a secondary world, what matters is that the characters grow and develop via the story to overcome problems and reach a satisfactory conclusion. Well, OK, the setting matters, but it’s not always the first thing that hits me. The setting and the detailed worldbuilding grows around the characters and weaves through the story, adding context and interest, and sometimes becoming a character in its own right.

So Empire of Dust, in a much earlier form, was finished in the late 90s and then began the rounds of publishers’ slushpiles. Remember what I said about persistence? Well, I’m dogged, but not always very pushy. Empire sat on one editor’s desk at a major publishing house for three years after the editor in question had said: ‘The first couple of chapters look interesting. I’ll read it after Worldcon.’ It took me three years to figure out I should withdraw it and send it somewhere else. Then the next publishing house it went to took another fifteen months. Those kind of timescales can eat up a decade very quickly. (I know one author who took to sending her languishing submissions a birthday cake after a year.)

In the meantime I kept on writing. It just so happened that the next three books were fantasies unrelated to each other: a retelling of the Tam Lin story aimed at a YA audience; a fairly racy fantasy set in a world not dissimilar to the Baltic countries in the mid 1600s, and a children’s novel about magic and ponies (not magic ponies). Why fantasy? I think I instinctively wanted to widen the scope of what I was doing to take in a wide variety of settings, however it was still mainly dictated by the characters.

If story and character are a universal constant, surely the difference between writing science fiction and fantasy is all down to worldbuilding. Right? Uh, well, maybe…. Science fiction can (to a certain extent) be fuelled by handwavium based on the accumulated reader-knowledge of how SF works. SF readers have an idea of how physics can be bent without being completely broken, whether you’re talking about the physics of Star Trek (warp-drives, photon torpedoes), or the hard SF of Andy Weir’s The Martian (which I love, by the way). When you write fantasy, you don’t have Einstein to fall back on. You have to work out how your fantasy world works from the ground up. If there’s magic, the magic system has to be logical and not contradictory (unless you build in a reason for the contradictions). If it’s set on a secondary world you might have strange creatures, races other than human, or even gods who act upon the world or the characters. Though, come to think of it, aliens, strange flora and fauna, and even ineffable beings are obviously common to science fiction as well. And when I said fantasy doesn’t have Einstein to fall back on, it does have the accumulated folklore of several millennia to point the way.

I think I’ve just talked myself round in a circle. So far, so similar.

So I started my next project, Winterwood, around 2008. By this time Empire of Dust had had three near misses with major publishers, but was still doing the rounds.

Winterwood almost wrote itself. I had the first scene very firmly in my mind – the deathbed scene – a bitter confrontation between Ross and her estranged mother. I wrote it to find out more about the characters and their situation. Ross hasn’t seen her mother for close to seven years since she eloped with Will Tremayne, but now her mother is dying. About halfway through the scene Ross’ mother asks (about Will): ‘Is he with you?’ Ross replies: ‘He’s always with me,’ and then follows it up with a thought in her internal narrative: That wasn’t a lie. Will showed up at the most unlikely times, sometimes as nothing more than a whisper on the wind. That was an Ah-ha! moment. I realised that Will was a ghost. Ross was already a young widow. That led me deeper into the story and gave me another character, Will’s ghost – a jealous spirit, not quite his former self, but Ross is clinging to him because he’s all she has left. That sets the scene nicely for when another man finally enters Ross’ life, but the romance is only part of the story. Ross inherits a half-brother she didn’t know about, and task she doesn’t want – an enormous task with huge consequences. There are a lot of choices to be made, and no easy way to tell which are the right ones. Ross has friends and enemies, some magical and some human, but sometimes it’s difficult to tell them apart. Even her friends might get her killed.

When that first scene came into my head, it could have been set in any place, any time. Parents and their children have been disagreeing and falling out for as long as there have been parents and children and, I’m sure, until we decide to bring up all our offspring in anonymous nurseries, it will continue well into the future. Ross took shape as I wrote, and I realised it was set in the past, or a version of it. In her first incarnation Ross was a pirate rather than a privateer, but I wasn’t sure what historical period to set the book in. The golden age of piracy was really in the 1600s, but I wanted to set this slightly later, so I decided that 1800 was a good time to play with. It’s a fascinating period in history with the Napoleonic Wars about to kick off in earnest, Mad King George on the British throne, the industrial revolution, the question of slavery and abolition, and the Age of Enlightenment. Of course I added a few twists, like magic, the rowankind and a big bad villain, who is actually the hero of his own story, though that doesn’t make him any less dangerous to Ross.

Historical fantasy is yet another subset of F & SF. If you’re writing in a specific historical period, you can make changes to incorporate your fantasy elements, adding magic for instance, or tweak one historical, point, but then you have to make sure that there’s enough solid historical background to make the rest of it feel authentic. You’re not necessarily looking for truth, but you are hoping for verisimilitude. I’m an amateur historian, not an academic one, but I did a lot of research: reading, museums, studying old maps and contemporary photos. I have several pinterest boards devoted to visual research, costume (male and female), ships, transport and everyday objects. Whenever I find something interesting I pin it for later consideration.

So where did we leave the publishing story? Oh, that’s right, Empire of Dust was doing the rounds of publishers’ slushpiles. While that was happening I submitted Winterwood to DAW and after about three months got that phone call that every unpublished author wants. Sheila Gilbert said: ‘I’d like to buy your book.’ One thing turned into another and before long I had a three book deal. As I said earlier, Sheila decided that Empire of Dust would be the first book out, even though it had been Winterwood that had initially grabbed her attention. Then she ordered a sequel to Empire, which was the book that became Crossways. If you want me to talk about writing a book to order, sometime, that would be another post altogether. Suffice it to say that Crossways came out in August 2015 and allowed me to take the stories of Cara and Ben to another level and move the setting from the colony planet to a huge, and vastly complex, space station, beautifully illustrated on the book’s cover by Stephan Martiniere.

So where did we leave the publishing story? Oh, that’s right, Empire of Dust was doing the rounds of publishers’ slushpiles. While that was happening I submitted Winterwood to DAW and after about three months got that phone call that every unpublished author wants. Sheila Gilbert said: ‘I’d like to buy your book.’ One thing turned into another and before long I had a three book deal. As I said earlier, Sheila decided that Empire of Dust would be the first book out, even though it had been Winterwood that had initially grabbed her attention. Then she ordered a sequel to Empire, which was the book that became Crossways. If you want me to talk about writing a book to order, sometime, that would be another post altogether. Suffice it to say that Crossways came out in August 2015 and allowed me to take the stories of Cara and Ben to another level and move the setting from the colony planet to a huge, and vastly complex, space station, beautifully illustrated on the book’s cover by Stephan Martiniere.

Getting a book from writer to store shelf is a multi layered process. There’s the writing and then the edit – which usually means some rewriting with additions. The once the final story has been accepted as finished it goes through copy-editing where clunky prose and spelling mistakes are smoothed over, and in my case, my British English is translated into American. Once the copy edits have been done then next part that I’m involved in is the page proofing, the final check after the book has been put into its finished form. This is the last chance to catch typos and brainos, but there’s no real opportunity to make big changes.

During the various editing processes there are gaps while your editor reads and considers, or the copy editor does his or her thing, so you tend to be working on other stuff while you’re waiting. The beginning of one book overlaps the editing process on the previous one and will in turn be at the editing and copy-editing stage when you’re just beginning to write the book after that. So, you see, it’s not like you have the luxury of working on one book at a time. The whole process is plaited together, fantasy and science fiction running alongside each other.

Winterwood comes out on Tuesday 2nd February. I’m currently writing Silverwolf, its sequel, which is due out late 2016 or early 2017. After that I’m contracted to write a third Psi-Tech novel (the aforementioned Nimbus), so it’s back to another space opera to follow on from Empire of Dust and Crossways. After that I’d like to write a third Rowankind novel. I already have ideas and there will be a few loose ends at the conclusion of Silverwolf, though, don’t worry, I never leave books on cliffhangers.

So the transition between science fiction and fantasy is not neatly delineated. It’s all mushed up together in both my writing timeline and in my brain. On the whole I just write stories set in different worlds. Some of them happen to have rocket ships, and others have magic, but all of them have characters who have adventures, relationships, and make choices, good and bad. I’m happy hopping between the future and the past, and I’m super-happy that my publisher has given me the opportunity to be an author who writes both SF and F.

You can keep current with all Jacey’s news over at her website.

P.S I’ve just finished reading Winterwood and can recommend it as highly as the Psi-Tech Novels.

Fight Like A Girl – the anthology and the launch event!

I honestly cannot recall what started that particular Twitter conversation. I’m guessing it was probably something about ‘fight like a girl’ being used as some throwaway insult, prompting derision from the very many of us women with hands-on experience of a broad range of martial arts and skills. Somehow – rather splendidly – the discussion morphed into ‘how about an anthology…?’

The rest is history. The future is this splendid book from Grimbold Books, who ask –

“What do you get when some of the best women writers of genre fiction come together to tell tales of female strength? A powerful collection of science fiction and fantasy ranging from space operas and near-future factional conflict to medieval warfare and urban fantasy. These are not pinup girls fighting in heels; these warriors mean business. Whether keen combatants or reluctant fighters, each and every one of these characters was born and bred to Fight Like A Girl.

Featuring stories by Roz Clarke, Kelda Crich, K T Davies, Dolly Garland, K R Green, Joanne Hall, Julia Knight, Kim Lakin-Smith, Juliet E McKenna, Lou Morgan, Gaie Sebold, Sophie E Tallis, Fran Terminiello, Danie Ware, Nadine West “

Fans of The Tales of Einarinn might like to note that my story, ‘Coins, Fights and Stories Always Have Two Sides’ takes place in during the Lescari Civil Wars, before the events of the Chronicles of the Lescari Revolution.

When can you get hold of a copy? Well, we’re launching the anthology with an event in Bristol on Saturday April 2nd from 1-5.30pm, at the Hatchet Inn, 27-29 Frogmore St, Bristol, BS1 5NA in association with Kristell Ink and Bristolcon. (Isn’t the collaborative, supportive nature of SF&F great?)

It’ll be a sociable and fun afternoon including swordplay and display, discussing the role of women in SF&F (both as characters and authors), excerpts from the book, and a buffet. Whether you’re a budding writer, established author or genre fan, there will be something for everyone!

You can book tickets here – please note that the £5 is to cover the cost of the buffet (and the 95 pence is Eventbrite’s administration fee). Overall, the event is being funded by the Bristolcon Foundation.

I’m really looking forward to it. See you there, to help fly the FLAG?

Creative writing articles – the latest link & a new permanent webpage to round up the rest

I’ve had a couple of invitations recently to write guest articles on different aspects of creative writing. You can find the first of them here at the SciFi Fantasy Network where I outline how I learned vital lessons about getting feedback, thanks to NOT getting published twenty years ago.

So that’s the first thing. Head on over and read that and feel free to pop back and let me know what you think. Meantime, on to the second thing here.

Looking for inspiration for these posts, I asked folks what would interest them and got a fine range of responses. Though in some cases, I thought, ‘hang on, haven’t I already written about that topic?’

A little research soon indicated that well, yes, I might well have written such an article but those pieces are not necessarily straightforward to find, especially when I wrote them over a decade ago!

It struck me pretty forcefully that a round-up was in order. I soon discovered that I’ve had good many and varied things to say over the years, but rather than bludgeon you with an endlessly scrolling blog post, a separate list would be more wieldy.

So here’s a dedicated page on the site to make everyone’s life that bit easier.

There’s a good range of reading for you to browse and dip into at your leisure, in roughly reverse chronological order, which is to say, the most recent at the top, oldest at the bottom, and including guest pieces by me elsewhere.

Below that you’ll find links to guest posts from other writers that have appeared on this blog.

Enjoy!

Western Shore. Mapping the Aldabreshin Archipelago and beyond.

‘Where did this unforeseen enemy come from?’ That’s the central question in this third novel of the Aldabreshin Compass quartet. Swiftly followed by ‘how did they get here?’, ‘why did they come?’ and ‘why are they so brutal?’

Kheda and his allies, old and new, discover most of the answers as Western Shore unfolds but before I could write any of that, I had to work out all these things for myself. Not only deciding where these unknown invaders did come from but establishing what had changed to enable them to cross the vast western ocean, since they’d never been seen before. ‘Well, they just decided to,’ simply wasn’t an option, any more than ‘because they’re just evil,’ is ever a satisfactory answer to ‘what makes the bad guys so bad?’

At least I had a map of the Archipelago to start with. I’d learned my lesson after having to reverse engineer the original Einarinn map from accurately calculated travel details in the text and my (literally) back-of-an-envelope sketch not long before The Thief’s Gamble was published. Okay, my husband had to do the actual work – I was and remain thankful that he’s an engineer whose apprenticeship including training as a draughtsman. Incidentally, he’s the one who insisted the Einarinn maps have projection lines, when I explained I needed a map which I could put a ruler on anywhere to measure distances on the same scale. He naturally felt thoroughly vindicated when we got an enthusiastically appreciative letter from a Geography Ph.D student in Washington State, USA, for whom flat-earth fantasy maps were a personal bug bear. But I digress.

As you see from this far more extensive map, I had the upper half of the Archipelago mapped by the end of The Tales of Einarinn, so extending the island groups and chains southward was easy enough. But then I had to decide what lay out to the west. ‘Here be dragons’ might be literally true but I needed to know where and why, and crucially, why they were on the move for the first time in more than living memory.

Because ocean and atmospheric currents had changed somehow? That looked like a promising possibility so I went off to do some research, including but by no means limited to buying The National Geographic Atlas of the Oceans and doing detailed searches through my National Geographic Archive CD-Roms. I learned all sorts of useful facts about jet streams, thermohaline circulation, deep cold water flows, tectonic plates and undersea ridges, as well as weather patterns, and what causes trade winds, the doldrums and El Nino. All fascinating and all terms and systems it would be impossible to reference directly in an epic fantasy novel without ruining, well, the atmosphere. This is definitely a situation where the Iceberg Rule of Research applied. Only a tenth of this work shows above the surface, which is to say, appears in the final novel, but that couldn’t be there without the other ninety percent.

Now I had the key information which I could add to my map and integrate into the story. More than that, I was now seeing more ways in which wind and sea currents and the distribution of islands would affect travel and alliances within the Archipelago. This work was already influencing the course of the events I had planned for Eastern Tide. It ultimately contributed to The Hadrumal Crisis as well but that’s another story.

But all this work stayed on the papers on my desk. When the Aldabreshin Compass was published in paperback in the UK, we were all forced to agree that the scale and layout of the Archipelago meant reproducing the whole thing at that page size could only offer readers a scatter of uninformative dots. When Tor produced the US hardback, they had more room to work with and included a very handsome map but that could still only offer a section of the Archipelago, unable to show its relationship to the mainland.

So only a limited number of fans got to see even that much. And as with the admirable Einarinn maps in the Orbit paperbacks, the copyright for that specific depiction of my original material remains with the publisher, not with me.

Well, that was then and this is now. As those who’ve bought Southern Fire and Northern Storm already know, these new ebook editions include a map of the entire Archipelago and now I’m adding it to the website. This time I have my elder son to thank, who took on the not inconsiderable task of cleaning up the digital scan of my master paper copy, with all its creases and pencil scribbles, as well as collating all the other bits of information jotted on sections I’d enlarged and printed off separately to cover with more coloured arrows and notes. Finally he added his own bit of artistic flair, deciding it needed to look like something found in a Hadrumal wizard’s archive, maybe left by some ambitious cloud mage seeing just how far up he could take a scrying spell. I reckoned he’d earned the right to do that.

So is this it? Well, as you can see, there’s still an awful lot of this world still to be mapped – and we haven’t even found out what might be happening in those lands we can already see but haven’t yet visited…

Guest Post – Tricia Sullivan on World Building and the Kobyashi Maru

Tricia Sullivan has a new book out this week, Occupy Me, and I think it’s fair to say her award-winning, idea-driven SF is worlds away from my own style of epic fantasy fiction. And yet, as is the case with a good many writers whose work is nothing like mine, we have a good few things in common; the foundation for our friendship and mutual respect. One of those things is a background in tabletop and computer gaming and Tricia’s written a fascinating article examining the relationships between that style of world building and truly creative writing.

Once you’ve read it, I’ll be very surprised indeed if you’re not prompted to find out more about Tricia and her work – if you’re not already familiar with her books!

“Kobiyashi Maru

Whenever somebody says ‘worldbuilding’ I think of Gary Gygax straight away. I think of polyhedral dice, graph paper maps for dungeons, hex paper maps for outdoors. I think of the languages I tried to invent and all that other good, ooky stuff.

I was a first-generation D&D player. My brother bought it in a box in 1979. I was in fifth grade, same year I read Dragonsinger, and I remember being genuinely scared by the giant spiders and ghouls in the sample dungeon. There were hardly any modules back then, so if you gamed you really had no choice but to make it all up yourself. D&D was a great enabler of storytellers. Its codification, numeration and classification of every damn thing both encouraged worldbuilding—by providing scaffolding—and also inhibited it—because D&D turned reality into a Lego set.

Don’t get me wrong—I’m very fond of Lego, but you have to admit the results are always pretty…well…square. D&D was square like that, too. I hated how designing anything in it was the equivalent of filling out 40,000 pages of requisition forms, ticking boxes all the way.

When you are building worlds, sometimes you want Lego, but other times you want Play-doh. Sometimes you want to be able to bend it and squish it. In the pre-digital era it used to be possible to express things without having to first establish the rules and the codes. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that D&D was coming in at the same time as Apple and Atari—it was more flexible than writing code, but at heart the game was all about the rules. And taken to the limit, the rules of the world can become more important than the thing you are trying to do.

Fictional worldbuilding is like that, too. You want the story to take flight in the reader’s imagination, but you never want the reader to see the billions of robots running around behind the scenes pulling leavers and heaving things into position. You’ve got to convince the reader they are immersed. How do you do that? I reckon you have to play with what people already know about the world—but of course, most of us don’t know very much! It’s interesting to me that one of the least conventional writers I can think of, Diana Wynne Jones, nevertheless authored ‘The Rough Guide to Fantasyland’ as a plea for at least a little rigour. To work well, fantasy has to stand on the shoulders of reality.

But what does rigour even mean, these days? Culturally, we have a certain D&D-based shorthand when it comes to kingdoms, quests, character classes and expectations—all mainstreamed thanks to video games. These archetypes are pretty distorted and some of them are tired as hell, but whether the shorthand is played straight or torqued in some way, it’s pretty much embedded in the DNA of SFF across all the platforms that now deliver SFF content.

The shorthand can be a great facilitator. As a writer, it’s not hard to use a prefab world and tweak it a little for your own purposes. It doesn’t take a big deviation in initial conditions from the world as we know it to a world that seems strange and new. Once you open up the toolbox (of environment, economic systems, biological structure, culture, history, yadda yadda yadda) you have endless permutations at your disposal to experiment with ‘what if’ and to run simulations—alternative worlds to our own, if you will. This is the primary function of imaginative play. It is also very hard work.

But causal extrapolation isn’t the end game, at least not for me. In fact, it’s often a trap, a dead end, an unwinnable situation. No, the end game is imagination. The end game is magic.

Real magic—if I can indulge in the oxymoron—isn’t systemized. It’s outside our understanding, by definition. It comes out of flashes of insight, surprise, transformation. To make those kind of fireworks go off in someone’s mind is a very tricky business, and I’d argue that to make it happen as a writer, you need total control and this includes knowing when to lose control. When to let go of the wheel. A world you’ve built becomes its own organism, has its own mind, and to give it lift-off there’s a point where you throw out the rules, throw out what you think you know, and let the thing take you where it needs to go.

Gaming doesn’t teach this, and as far as I know it’s not in the Dungeon Master’s Guide, but I’ll bet artists know what I’m talking about because they build worlds, too—that’s what art is. Even as it’s using rules, art is a protest against the rules.

If you really want to fly, then just for a moment, get meta. Don’t accept the limitations you’re given. Reprogram the fucking computer that your world is running on. Beat the Kobiyashi Maru.

The dice and the graph paper will still be there when you come down.”

You can find out more about Tricia, her writing and this book in particular, over at her website

Are we finally seeing the long-overdue examination of what’s gone wrong with the book trade?

Philip Pullman and those writers backing him (referenced in my previous post) seem to have prompted an important – and to my mind, long overdue – examination of exactly what’s gone wrong with the book trade in the past five or ten years.

From Nick Cohen, on his experience of being asked to appear at The Oxford Literary Festival. ‘Why English writers accept being treated like dirt’

For those who don’t have time to read the whole thing just at the moment, the key quote for me is as follows:

If the system does not change, readers will suffer for a reason that cannot be repeated often enough. The expectation that workers will work for nothing is leading to the class cleansing of British culture. Everywhere you go, you hear culture managers saying they want ‘diversity’, while presiding over a culture that might have been designed to exclude the working and lower-middle classes. Whether you look at journalism, the arts, the BBC, photography, film, music, the stage, and literature, you see that those most likely to get a break are those whose parents are wealthy enough to subsidise them. The generalisation is not wholly true. Young people from modest backgrounds can still break through. But every year their struggle becomes a little harder. Every year, an artistic career becomes a little less viable to potentially talented writers and artists.

From Philip Gwyn Jones, laying bare the implications for readers. ‘The civil war for books; where is the money going?’

Though this post isn’t just about money. It’s about the ways changes in bookselling influence publishing decisions and ultimately limit readers’ choices. Once again, until you can find the time to read the whole thing.

as a commissioning editor and publisher of some 25 years standing, I hope I have some authority to make the claim that certain stars are missing. They are just not being born. It seems to me that there is a universe of self-censorship out there, even if it is invisible to the naked eye. We’ve had perhaps five years now of good writers taking their next ambitious project to their agent who in turn excitably puts it in front of publishers only to be told that it’s perhaps a little too bold an idea for these austere and shape-shifting times, and might there not be a more reader-friendly project up the writer’s sleeve? The agent sheepishly reports this back to their beloved writer, who then either conforms to the market’s demands or slopes away to nurse their wounded ego, and think hard about the purposes and pleasures of writing. The next time that writer comes up with a bold, unorthodox, unprecedented notion for a book, what happens? Well, perhaps, just perhaps, they decide before they start in earnest that it’s a no-hoper and they ought to play safe, so they bin it without telling anyone. And another bright star never shines.

…

Social reading is the coming thing, we are told, where our reading devices and apps will allow us to communicate with others who are reading the same book we are, share notes and queries with them, correct and conject, exult and excoriate together as if we online readers were round a digital dining table, and even involve the writer in that conversation if they are willing. But for such Social reading to work, everyone has to be reading the same thing, so it tends to favour the popular, the shared, the already-known. Hence the ubiquity of Most Read and Most Liked lists. There is a lot of barked coercion out there in cyberspace. So the online sharing book economy will coalesce around, well, winners. But what happens to the losers: the unshared, the jagged, inimitable, harder-to-chat books?

And the next time you’re in your local High Street or supermarket, take a look at the books on offer and I’m pretty sure you’ll see all these forces already at work.

Which incidentally, brings me back to something important about SF conventions and the genre small press. Both continue to support and promote writers and books outside the mainstream, thanks to the support of readers looking for something beyond mass market fodder.

Key differences between Literary Festivals and SF Conventions when it comes to payment

I’m extremely pleased to see Philip Pullman making a stand on the issue of literary festivals not paying writers – when everyone else involved gets paid – and to see a host of other authors backing him.

But I am also seeing a degree of confusion, particularly from SF&Fantasy fans/writers who think this is a call to pay programme participants at SF conventions. Some clarification may be useful. As well as regularly attending conventions, I’ve long been involved with non-genre literary festivals thanks to working with The Write Fantastic and also as a committee member for my old Oxford college’s Media Alumnae Network. Consequently I have observed how very different their approaches are.

Literary festivals organise their programming primarily around publishers’ schedules and offer one or two writers per slot an opportunity to publicise their current book. The biggest names with the highest media profiles get the biggest venues and the best time slots because these are commercially-minded enterprises whether or not they’re structured as charities like the Oxford Literary Festival. Everything from venues to publicity to technical support must be paid for and that means selling tickets to fill the seats. None of this is criticism. I always enjoy hearing a talented author share their enthusiasm for their work, fiction or non-fiction, as I sit in a quietly attentive audience. And yes, the big name events do help fund the lesser known and special interest authors’ events – such programming is assuredly valuable for readers and writers alike.

But make no mistake; this is work for an author. It’s essentially an hour’s professional performance or presentation. It’s just not treated as such. Over the years, as a contributor at assorted festivals, I’ve turned up, got a cup of coffee in the green room, done my thing, and that’s pretty much that. Depending on the time of day I might be offered access to a buffet lunch (problematic for anyone with dietary issues). I’ve generally had my travel expenses covered but in all but a very few cases, I haven’t been paid for my time on the day or for the essential preparation. And no, the royalties I might get from however many of my books are sold at the festival wouldn’t come anywhere close to a reasonable fee. I might get a ‘goody bag’ with something like a bottle of wine, maybe some perfume, and a couple of books (which alas, I seldom actually want). I would usually get one or two complimentary tickets for my own event, nice for friends and family, but if I want to go to any of the festival’s other events, I have to buy tickets like any other punter.

SF conventions are very different. From their earliest days, conventions have been fan-led events. Readers and writers alike are encouraged to get involved, exploring their shared enthusiasm. Those going to SF conventions pay for memberships rather than tickets. People aren’t buying a seat to passively attend a one hour event. They’re investing in the funding of a collective enterprise over several days, run by volunteers for fellow enthusiasts.

A weekend’s membership gives access to dozens, even hundreds of programme items. There are fact-based sessions, where fans and authors alike share their knowledge and expertise on everything from science in all its ramifications to historical, linguistic, political and psychological scholarship – just a few disciplines which underpin the ever-broadening scope of speculative fiction. As well as sessions exploring creative writing, programme items explore visual skills and disciplines from fine art providing inspiration to writers and artists alike, to comics and graphic novels. There’s discussion of SF and fantasy in film, TV and audio drama, from author and audience perspectives. Then there’s the fun programming, including but not limited to games and costuming events, ranging from the admirably serious to the enjoyably daft.

At a literary festival it’s rare to see a handful of writers talking more generally about their writing, about the themes and topics which their broader genre is currently addressing, about on-going developments in their particular literary area, comparing and contrasting their own work and process with each other and with the writers who’ve gone before them. It does happen, particularly with crime writers, but it’s still nowhere as prevalent as it is at SF conventions. I think that’s a shame, because audiences so clearly appreciate such wide-ranging discussion. It’s rarer still to see a fan/reviewer taking part in literary festival panels to broaden the debate with their perspective whereas such participation is an integral and valuable facet of convention programming.

Traditionally, at SF conventions, no one gets paid for the considerable amount of time they contribute, by which I mean none of the organising committee or any of those people who help out with such things as Ops, Publications, Tech and any amount of other vital support. Membership revenues cover the costs of venues and the various commercial services essential for the event to take place. Those authors who have been specifically invited as Guests of Honour have their expenses covered as a thank you for what will be a hard working weekend but they’re not paid a fee as such. Some conventions offer free memberships to other published authors on the programme and believe me, that’s always very much appreciated, but even then, those writers are expected to cover their own travel, hotel and sustenance expenses.

Is that fair? Well, an author assuredly has the opportunity to get far more from a convention than they do from a literary festival and not just a thoroughly enjoyable social event. It’s a weekend of networking and catching up on industry news, of benefiting from other writers’ experiences and perspectives, of learning things that are often directly relevant to whatever they’re working on or which will spark their imagination for a new project, of engaging with established fans and readers new to their work, often getting valuable feedback and usefully thought-provoking questions. Opportunities for paying work often follow from contacts made and conversations had.

Which is great – as long as you can afford to get to the convention in the first place and with authors’ incomes dropping year on year, that’s becoming an increasing issue for many SF&F writers. Plus the line between fan-run, non-profit events and overtly commercial enterprises has become blurred in some cases in recent years. I’ve been invited to SF&F events where I’ve discovered media guests are being paid fat appearance fees but the writers are expected to participate for free, in some cases without even expenses paid. You won’t be surprised to learn I declined. Then there have also been events where I’ve discovered some writers’ expenses are covered at the organisers’ discretion – but not others. That’s wholly unacceptable as far as I am concerned.

So do I think writers appearing at literary festivals should get paid? Yes. They’re doing a job of work to a professional standard and everyone else involved is getting paid.

Do I think programme participants at SF conventions should be paid? In an ideal world, yes – but doing that would force up the cost of convention memberships far beyond what the other fans could afford, especially once their hotel and other expenses are factored in.

Should all conventions factor in the cost of free memberships for programme participants? Personally, I’d very much like to see it. It’s saying ‘this is the value we put on your contribution and thank you’ as opposed to ‘kindly pay us for the privilege of working this weekend’ but once again, that would force up the cost of membership for everyone else with implications for levels of attendance and thus funds for essential expenses. Some conventions will decide their event can sustain this, others will decide that they can’t. As I know from my participation in running Eastercon 2013, a big convention’s budget is a dauntingly complex affair.

But the crucial distinction remains. Literary festivals and other commercial enterprises should pay the writers without whom there’d be no event. Non-profit conventions where readers and writers are sharing their common passion as fans are something else entirely.