Category: Guest Blogpost

Guest post – Dan Jones on his “Journeys” story

One of the many interesting things about writing for an anthology is encountering new-to-me authors’ work, and thanks to the wonders of the Internet, getting to know those authors themselves. Here are some interesting thoughts and observations from Dan Jones on his own path to having a story in the new Journeys anthology.

Dan Jones on his “Journeys” story – and the importance of the one before that…

When Woodbridge Press announced their open call for their forthcoming fantasy anthology Journeys, back in Spring 2016, I was immediately hooked. A stellar line-up had already been secured, including such illuminaries of the genre as Julia Knight, Adrian Tchaikovsky, John Gwynne and Gail Z. Martin – not to mention our esteemed editor Teresa Edgerton – and so I decided I would apply.

My successful submission to Journeys capped off an interesting learning experience: I had just come off the back of a rejection from Woodbridge for their previous call for submissions for the excellent Explorations: First Contact, for which I’d submitted a short story that was ultimately rejected for being not mainstream enough for the collection.

It’s highly tempting for us writers to sometimes get lost in our art, to spend so long considering the deep thematic resonance, the recurring motifs, the profound messages that occasionally we forget such fundamentals as a compelling plot and interesting characters; I am definitely guilty of sometimes getting a bit overexcited about form and structure, and it came back to bite me with that particular rejection.

For the next call, I cast aside my pretences, and for Journeys I decided to write a simple, rollicking adventure story, and it got accepted. It’s a worthwhile thing to remember: know your audience, write for your audience, and keep it simple.

Well, at least start simple, and then add the flourishes when you have the basics in place. My Journeys story, A Warm Heart, started with a very simple premise; a world-weary assassin-in-training, Tarqvist, is unwillingly joined by an unexpected companion on his first assignment, a wise-cracking, annoying and arrogant young girl he calls Nobody. From this simple set-up almost anything is possible, and it was liberating to consider all the fun things, like theme and structure, once the initial foundations were sound.

Conversely, if I think back to the story that was rejected for Explorations, I was more interested in establishing the structure first – a non-linear sequence of dream-like scenarios – and only applied plot and character afterwards, and it must have showed. It’s a well-known trope among writers that there really are only a small and finite number of plots (Christopher Booker famously posited that there are in fact only seven), so it stands to reason that establishing your plot (and the characters who will travel along that plotline) should be the first thing to get right before one starts dabbling in the trickier arts of form, structure and theme.

I’m super grateful for that rejection, as it taught me a valuable lesson and helped shape the story that now sits inside this superb collection of stories and authors, which I’m proud and exhilarated to be a part of. What’s more, it’s one of a handful of books I’ll be having published this year, including my debut novel, Man O’War, to be published by Snowbooks in October, so it’s a grand start to the year for me personally.

It’s fitting that the theme for the collection is Journeys, as I feel as though I’ve been on my own mini-quest in getting here, just as have all the other authors, I’m sure. We’re all journeymen in this business, you know.

Dan Jones is a science fiction and fantasy writer, but when not writing he works for the UK Space Agency on a space robotics technology programme, which comes in rather handy for coming up with new story ideas. His debut novel, Man O’War, will be published in October 2017 by Snowbooks.

Twitter: @dgjones81

website: www.danjonesbooks.com.

Guest Post – E.C. Ambrose on the challenges of getting the words right in a historical novel

When she graciously invited me to visit on her blog, Juliet expressed some frustration over the problem of words—specifically, genuine, specific and appropriate words that we’re just not allowed to use, or must work in very carefully. She invited me to comment on the problem of words. Not long ago, working my way through my editor’s notes on Elisha Mancer, this month’s release in The Dark Apostle series, I encountered first hand the difficulty of words. Words are, in a novel, the primary tool for delivering the story. In a historical novel, they take on a special significance because selecting an appropriate word for the historical context can really make the sentence spark and the work feel right. And selecting the wrong word will annoy readers in tune with the history.

Which brings me to the problem of plagues. The Biblical plagues of Egypt, for instance. In modern parlance, “plague” retains a similar sense: a plague is, as the OED puts it, “an affliction, calamity, evil, scourge” (a plague of locusts, a plague of survey callers, etc.) But many readers of medievally set historical fiction immediately leap to a single meaning of the word, which came into use around 1382 to refer to a pestilence affecting man and beast. And “the plague” wasn’t conceived as a specific entity until the 1540’s. But basically, I can’t use the word in its historically accurate sense.

My difficulty with language then versus now doesn’t end with the plague. There is also the problem of things being lost in translation. Saints, that is. While we now use the word “translate” to refer exclusively to taking words or ideas from one language into another (sometimes metaphorically), the origin of the term is actually the transfer of a religious figure from one location to another, as a bishop who moves to a different see, or, more frequently, a saint or saint’s remains taken to a different church. It is this idea of holiness being moved or removed which brought the word to its present meaning, because the most work common work translated was the Bible itself.

“Broadcast” is another interesting example. Nowadays, we are used to “broadcast” news, a television or radio phenomenon by which information is shared. It’s actually a farming term, referring to the sowing of seeds by hand over a large area–the literal casting of the seed in a wide dispersal. But most readers, finding the word in a medieval historical context would leap to entirely the wrong impression, thinking I am using an anachronism. And so, rather than submit to a plague of criticism, I had to use something less historically appropriate, but more suitable to a contemporary audience.

This problem of words first arose in Elisha Barber, volume one of the series, when I referred to someone as a “blackguard,” a useage which can’t be traced to before the 16th century (my editor has an OED also, which is both blessing and curse). I ended up changing the insult to “chattering churl,” which not only employs a 14th century jibe, but adds to it the tendency to use alliterative insults from the same time period. Stretching for the historically appropriate choice actually resulted in an even more historical put-down.

As you can see, there are multiple layers to this dilemma. Is the word historically accurate? Will my readers understand it? Does it have contemporary implications that were not present in the period, but will complicate or undermine my intended meaning?

My series is based around medieval medicine, and surgery in particular, requiring some amount of period jargon appropriate to the profession. In this case, I rely strongly on context to invest the reader in the words. Sometimes, I can use the reaction of another character—their horror or confusion providing an innocent to whom the word can be explained. Sometimes, the meaning becomes clear as the action proceeds, and sometimes, the specific meaning is less important than that the new word becomes part of the framework of history on which the tale is woven.

In this case, I didn’t explain all of the unfamiliar terms surrounding the operation. Part of our fear of doctors stems from the fact that we don’t always understand what they say, yet we also know we need to trust them. We submit ourselves in part because of their professional demeanor, and jargon in this case is both symbolic of the doctor’s training, and of our own helplessness beneath the blade. Those mixed emotions of trust and dread link the reader’s experience with that of the character and, I hope, create a compelling scene—because of the right word, in the right place and time.

Want to know more? For sample chapters, historical research and some nifty extras, like a scroll-over image describing the medical tools on the cover of Elisha Barber, visit www.TheDarkApostle.com

E. C. Ambrose blogs about the intersections between fantasy and history at http://ecambrose.wordpress.com/

See also –

https://twitter.com/ecambrose

https://www.facebook.com/ECAmbroseauthor

Buy Links for volume one, Elisha Barber:

Indiebound

Barnes & Noble

Amazon

Guest Post – Gaie Sebold on Villainous Pleasures

With a week away now in sight at the end of the month, I’m stockpiling holiday reading. One book I’m very much looking forward to is Gaie Sebold’s ‘Shanghai Sparrow’. I really enjoyed her Babylon Steel books – an entertaining and intelligently different take on epic fantasy. So it’s going to be fascinating to see what she does with the themes and ideas of Steampunk and I’ve invited her to share some thoughts on the book here. Over to Gaie.

Villainous Pleasures

Villainous Pleasures

When I started writing Shanghai Sparrow, the first book in the Gears of Empire series, I knew I wanted to write about the grimy, smelly, exploitative underside of the Victorian period. This may have been at least partly in response to a certain writer’s remark about Steampunk being ‘fascism for nice people,’ which, as a longstanding Leftie, I regarded as…well, more of a challenge than anything.

So my heroine, while originally from the most respectable of backgrounds, ends up surviving on the streets of London under the kind of circumstances that inspired Thomas Barnardo to set up his children’s homes. Evvie, however, did not meet Thomas Barnardo. She met Ma Pether, a woman who runs a group of female pickpockets, fraudsters and breakers-and-enterers.

I wasn’t expecting Ma. She created herself on the page, striding in, pipe asmoke, fidgeting dangerously with explosive mechanisms and creating bizarre aphorisms. She turned out to be a lot of fun to write. Almost too much fun – it was difficult to stop her taking over every chapter in which she appeared.

The same could be said to apply to the villainous Bartholomew Simms – though unlike Ma, he can’t really be said to have any redeeming features. At all. A thoroughly nasty, dangerous, sly, violent and brutal man – but with a certain style and turn of phrase that makes me look forward to writing him.

And then there’s Evvie herself – who occasionally aims for respectability but just isn’t terribly good at it. She’s too good at being bad, too good at fraud, deception, and thievery.

But she is the heroine. She has moral boundaries and dilemmas, she has struggles with her conscience. Just not always, perhaps, the same ones that most of us might have when faced with whether or not to nick something or rip someone off.

Yet she’s most fun to write, in some ways, when she’s just enjoying being good at what she does best – being a trickster and a thief.

And therein lies the question. Why are villains such fun to write? What is the appeal of going outside the moral boundaries within which I live quite happily most of the time in the real world?

I’m talking about my own personal moral boundaries, of course, which while they are going to overlap with many people’s are not always going to be identical. But I don’t steal, or commit fraud, or act violently to others. I don’t, as a general rule, want to. I fear the consequences, yes, but also, I don’t want to be a con-artist, a fraudster, a murderer. In real terms these are people who damage lives or end them, and I don’t want to do that.

And yet, on the page … it’s so damn much fun writing people who don’t have those boundaries. People who say those things, and do those things, and (sometimes) get away with it. But the point isn’t necessarily whether they get away with it in the long run – the fun part is that they get to say it and do it right now, right there, before our very eyes!

Some of it, certainly, is a form of wish fulfilment. I’d sometimes like to treat the law like the ass it occasionally, indisputably is. I’d often like to be able to turn the tables on our Lords and Masters, who rip off whole societies, whole countries, by outdoing them at their own game of fraud, deception and theft, but with a fraction of the resources and ten times the wits.

I might not want to murder, but I would like to be that bold, that scary, that tough. Especially when the vicious and violent of the world are making me feel threatened, I’d like, for once, to be the one who has conversations fall silent and glasses slip from trembling fingers when I enter the room, to be able to quell would-be opponents with a glance, to have my reputation go before me as someone not to be messed with.

I’d like the power that comes with going outside the legal and moral boundaries. But since I’m not going to do that, I have to find another way. And until the world becomes a place where (all questions of hard work and persistence aside), being nice and obedient and lawful is the best way for a woman to get respect, I guess I’ll keep on living vicariously through my villains, and enjoying every moment of it.

Gaie Sebold was born some time ago, and is gradually acquiring a fine antique patina. She has written several novels, a number of short stories, and has been known to perform poetry. Her debut novel introduced brothel-owning ex-avatar of sex and war, Babylon Steel (Solaris, 2012); the sequel, Dangerous Gifts, came out in 2013. Shanghai Sparrow, a steampunk fantasy, came out in 2014 and the sequel, Sparrow Falling, in 2016. Her jobs have ranged from till-extension to bottle-washer and theatre-tour-manager to charity administrator. She lives with writer David Gullen and a paranoid cat in leafy suburbia, runs writing workshops, grows vegetables, and cooks a pretty good borscht.

Her website is www.gaiesebold.com and you can find her on twitter @GaieSebold.

Guest post from Gail Z Martin – When The End Comes

Getting the final volume of The Aldabreshin Compass out in ebook has set me thinking about the challenges for a writer when it comes to concluding a series. Since I’m always interested to know what other authors think about a topic that’s got my attention, and noticing her current epic fantasy story is now reaching its own conclusion, I invited Gail Z Martin to share her thoughts on this particular topic. As you’ll see from reading this piece, that was an email very well worth me sending.

When the End Comes

By Gail Z. Martin

Saying goodbye is hard, especially to the people who have been living in your head.

Ending a series is bittersweet, because it brings a story arc to a conclusion, but it often means that those characters who have been in your thoughts every day for years, maybe decades, won’t be hanging out with you anymore.

So how do you wrap up a series in a satisfactory way, and in today’s digital publishing world, is goodbye ever really forever?

I’ve put a bow on two series now: The original Chronicles of the Necromancer/Fallen Kings Cycle series that runs from The Summoner to The Dread, and the Ascendant Kingdoms Saga series that ranges from Ice Forged to Shadow and Flame. I’m happy with the outcome in both cases, but it’s always sad to reach the end of the journey.

As a reader, I still feel sad thinking about series that ended the adventures of characters I’d come to love, like the Harry Potter series or the Last Herald Mage series. The series came to a planned conclusion, but it was still sad nonetheless that we wouldn’t be going on new journeys together. Having those experiences helps me make my own decisions as an author to give readers the best wrap-up possible and leave the characters at a good stopping point.

For the record, I think the whole debate about ‘happy endings’ is bull. A book’s ending is an arbitrary point chosen by the author. In the real world, we all have good days and bad days. If we are telling a story and chose to end the write-up on the character’s wedding day or the birth of a child or a big business success, that would be a ‘happy ending’ but it doesn’t ensure that tomorrow the character wouldn’t be hit by a bus, which had the story continued would make it a ‘tragic’ ending. That’s why I don’t think happy endings in and of themselves, properly led up to and reasonably executed are unrealistic. It’s an arbitrary decision of when we stop rolling the film on our character’s lives and let them go their way unobserved. I don’t buy into the idea of tragedy being more real or honest than happiness, or that a tragic ending is more legitimately literary than giving your characters the chance to go out on a good day.

So here’s what I think matters when it comes to wrapping up a series or a multi-book story arc:

1. Wrap up the loose ends. Make sure you’ve got all the characters accounted for, the plot bunnies caged, and the stray threads tucked in neatly. Don’t leave us wondering ‘whatever happened to …”

2. Give us closure. It may turn out that fate and free will are illusions and everything is mere random chance, but if it does, human minds will still be driven to assign meaning and context. So whatever journey or quest your characters have taken, make sure that by the end, we know what it all meant and what comes from it. Leave us with a sense of purpose.

3. Glimpse the future. None of us knows what tomorrow brings, but that doesn’t stop us from making plans. So have your protagonist face the future with the intent to move forward, and let us know what that looks like.

4. Provide emotional satisfaction. If you’ve made us care and cry and laugh and bleed for this character, then the least you can do is give us the emotional satisfaction of knowing how the character feels when it’s all over, and perhaps how the other key characters feel as well.

Now for the second part—do we ever have to really reach the end? Thanks to ebooks and the advances in self publishing, it’s possible for authors to continue to create new adventures in series long after the books are out of print or a series has officially ended. After all, authors can make a profit off self-pub sales levels that are far below what a traditional publisher considers viable. Readers love to get additional canon stories. And of course, there are also a growing number of book series that have been reanimated by new writers (Dune, for example) after the original author dies.

I truly think that series extension via ebook is going to continue to grow. There’s a lot of upside, and very little downside. I’ve written three novellas in my Ascendant Kingdoms world that fill in part of the six-year time gap that occurs early in Ice Forged, and I have another three in mind for later this year. (The three stories currently available are Arctic Prison, Cold Fury and Ice Bound, and the coming-soon collection of all three is The King’s Convicts.) They’re every bit as much ‘canon’ as the books, but they’re extra stories that flesh out characters and set up later events.

Likewise, my Jonmarc Vahanian Adventures are prequels to The Summoner, adding up eventually to three serialized novels of backstory for a very popular character. So far, there are 18 short stories and there will be three more novellas by the end of the year. And in the case of the Jonmarc stories, the original publisher asked to do a collection of the first ten short stories plus an exclusive eleventh and bring out the collection in print and ebook (The Shadowed Path, coming in June 2016). That’s a win for me, for readers and for the publisher, because it keeps existing fans happy while potentially bringing in new fans, and it helps me keep a light on for the characters until I get to write the other six books in the series that are bouncing around in my brain.

So there you have it—goodbye doesn’t have to be forever. Every series ending is the beginning of a new series extension. Virtual immortality, for our virtual characters. Seems like a win-win-win to me!

About the Author

Gail Z. Martin is the author of Vendetta: A Deadly Curiosities Novel in her urban fantasy series set in Charleston, SC (Solaris Books); Shadow and Flame the fourth and final book in the Ascendant Kingdoms Saga (Orbit Books); The Shadowed Path (Solaris Books) and Iron and Blood a new Steampunk series (Solaris Books) co-authored with Larry N. Martin.

She is also author of Ice Forged, Reign of Ash and War of Shadows in The Ascendant Kingdoms Saga, The Chronicles of The Necromancer series (The Summoner, The Blood King, Dark Haven, Dark Lady’s Chosen); The Fallen Kings Cycle (The Sworn, The Dread) and the urban fantasy novel Deadly Curiosities. Gail writes three ebook series: The Jonmarc Vahanian Adventures, The Deadly Curiosities Adventures and The Blaine McFadden Adventures. The Storm and Fury Adventures, steampunk stories set in the Iron & Blood world, are co-authored with Larry N. Martin.

Her work has appeared in over 25 US/UK anthologies. Newest anthologies include: The Big Bad 2, Athena’s Daughters, Unexpected Journeys, Heroes, Space, Contact Light, With Great Power, The Weird Wild West, The Side of Good/The Side of Evil, Alien Artifacts, Cinched: Imagination Unbound, Realms of Imagination, Clockwork Universe: Steampunk vs. Aliens, Gaslight and Grimm, and Alternate Sherlocks.

Find her at www.AscendantKingdoms.com, on Twitter @GailZMartin, on Facebook.com/WinterKingdoms, at DisquietingVisions.com blog and GhostInTheMachinePodcast.com, on Goodreads and free excerpts on Wattpad

Guest post – Zen Cho on ‘My Year of Saying No’.

You’ll recall how much I enjoyed reading Zen Cho’s debut novel, Sorcerer to the Crown. (If you missed my review, click here) So I’m extremely pleased to host this illuminating and thoughtful post reflecting on that story’s origins and her experiences as a newly published writer.

My year of saying no

In 2015 I became super obsessed with the BBC miniseries Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell. This wasn’t terribly surprising – I love the book and have reread it several times, and the series had everything I like: men and women in pretty period outfits, magic, humour, and even a touch of the numinous. It wasn’t a perfect adaptation, but an adaptation that’s sort of almost there but not quite is perfect for inducing fannish obsessiveness.

What was new and surprising was that, for the first time, I started identifying with Jonathan Strange. Jonathan Strange is nothing like me. He’s a fictional rich white dude who would be dead now if he was ever alive. I’m a real middle-class Chinese Malaysian woman who’s only spent time in 1800s England in her imagination. He’s the Second Greatest Magician of the Age. I’m a lawyer who moonlights as a moderately obscure fantasy writer.

I’m also fundamentally not as much of a douche (I love the character, but it’s gotta be said). I take no credit for this. It is because I was socialised as a woman and was therefore taught things like listening skills and how to feel guilty for taking up space in the world.

But there was one big thing I had in common with Jonathan Strange. We had both figured out what we’d been put on earth to do, and we were doing it. The vocations we had each chosen were potentially of great value and importance to society as a whole — magic in Jonathan Strange’s case; writing in mine — but we were mainly doing it for selfish reasons rather than to benefit anyone else. Nevertheless our work felt like a great and serious charge, and what this charge required of us was a determined selfishness.

In 2015 my first novel came out. It was a bit like getting married: it meant that something that had been private suddenly became very public, and people treated me differently about something I’d been working away quietly at for years. And it also meant that people started wanting stuff from me. They wanted me to answer questions, write blog posts, submit to anthologies, show up to events, blurb books, critique manuscripts ….

In 2015 my first novel came out. It was a bit like getting married: it meant that something that had been private suddenly became very public, and people treated me differently about something I’d been working away quietly at for years. And it also meant that people started wanting stuff from me. They wanted me to answer questions, write blog posts, submit to anthologies, show up to events, blurb books, critique manuscripts ….

It’s nice to be wanted, of course, and it was a refreshing novelty. As with most writers, rejection is the backing track of my life, so it was nice for once to hear “please will you?” instead of “no, thank you”. But it meant I had more demands on my time than ever before, when I had less time than ever before.

I had to learn to say no. Which was hard, because women aren’t encouraged to say no, and they especially aren’t encouraged to refuse to help other people. We’re supposed to be nurturing. Fortunately, I am pretty bad at being nurturing, but even so I struggled.

A lot of the requests I get are for nice things, things that support diversity in SFF and publishing, which is something I both care about and benefit from. How could I refuse when it was for such a good cause?

But I realised that if I was not ferociously protective of my time — if I didn’t play that role of The Rude Genius — I would soon find it sucked up in mostly uncompensated labour, in things that weren’t writing my own stories.

I don’t, in fact, have a room of my own. I have a sofa and an inbox full of requests for publishing advice that the querier could Google for themselves. So I’m learning to patrol the boundaries of the uncluttered space I need for writing — and for living, because I don’t owe anyone time and attention even if I’m not rushing to meet a deadline.

I’m still not as good at saying no as I should be, but I’ve already been accused of being grand for the appalling crime of not answering emails. I wonder whether the same accusation would be lobbed at me if I was a white man. We expect men, especially white men, to be rude geniuses. But it seems we feel entitled to the time and energy of women, especially Asian women.

You’ll point out I’m not a genius, which is true, but then I’m also not that rude. I say yes far more often than I say no. There’s still that fear, whenever I turn something down, that I should make the most of any attention I’m getting now, because people will stop asking eventually.

But you know what? I have never, not once, regretted saying no. And even if people stop asking and go away, it’s not like they’ll take the stories with them. Writing is mine – and it would be foolish to let a general sense of obligation to the world at large chip away at it. Jonathan Strange would definitely say something sardonic about that.

Guest post – Simon Morden discusses Down Station and portal fantasy.

A new book that I very much enjoyed reading this month is Simon Morden’s Down Station. For a fuller assessment, you can read my review in the next issue of Interzone.

A new book that I very much enjoyed reading this month is Simon Morden’s Down Station. For a fuller assessment, you can read my review in the next issue of Interzone.

For those of you unfamiliar with Simon’s work, his website is here – and for a chance to meet him, along with Tricia Sullivan, author of Occupy Me, they’re both signing at Forbidden Planet, Shaftsbury Avenue, London on 20th February, 1-2pm. Simon will also be a guest at the Super Relaxed Fantasy Club on 23rd February.

One of the things that particularly interests me about Down Station is the fact that it’s a portal fantasy. So I invited Simon to share some thoughts on that particular topic.

In defence of Narnia and other portals Simon Morden

I recently discovered that Narnia* is a real place. Quite how that fact has eluded me for my entire adult life is a complete mystery, but I have a sudden hankering to go there and make an in-depth investigation of their wardrobes.

Because you would, wouldn’t you? Or did you grow out of that urge? The ghost of the Susan argument rears its ugly head: wanting to escape this world, with its social and economic obligations and constraints, is something that a child would do, kicking against the goads of adulthood. When a person knows their place in society and accepts it, they no longer need such escapist diversions.

Lewis, however, was speaking of a more fundamental truth even as he got it hamfistedly intertwined with 1950s social mores. Rather than agreeing that wanting to escape to another place is a mere childish notion, to be discarded as we embrace a more mature understanding of our own world, he was proposing that it’s us – the grown ups – who are the ones who lose out.

The belief that our world lies side by side with others wasn’t invented by Lewis. It goes far back, beyond recorded history. In my native islands, the Celts believed the Otherworld was connected to us at certain times of year and in certain sacred places. People could cross over, usually by invitation rather than trickery, and sometimes even return. With the coming of Christianity, these became the ‘thin places’, where Heaven and Earth pressed together, but the result was always the same: those who came back were forever changed, either by their experience of the Other, or of the Divine.

Throughout history – and prehistory – the point of these stories was that the intrepid travellers to other worlds were never escaping: they were questing. They went for a reason – either to gain something which could be used in our world, be it wisdom, a skill, or an artefact, or to give something to that other world, to save it from evil or break a curse. That we’ve turned – some might say corrupted – an important facet of our mythology into a genre that adults shouldn’t consciously entertain is problematic, to say the least.

At its worst, yes, Sturgeon’s Law (that 90% of everything is crap) applies. A portal fantasy can be all those things their critics say it is: cliche-ridden wish-fulfilment in which nothing is at stake. Perhaps, after a while, these overwhelm the market and the whole genre goes out of fashion. Certainly, anecdotally, portal fantasies have been a tough sell for years. There were always exceptions: May’s Pliocene Saga and Pullman’s His Dark Materials being perhaps the most notable. But here we are, like buses, with two coming along at once, my Down Station and Seanan Mcguire’s Every Heart a Doorway. We’re probably at the cutting edge of a new wave, and editors across the land will hate us in six months’ time for unleashing a torrent of portals across their desks. For now, though, they represent something different to the usual fare.

I would like to think I’ve done something new with my own portal(s). Featuring non-standard protagonists is a start, being chased across the threshold is another, and the world of Down itself owes more to Tarkovsky’s Solaris than it does Narnia. But I’ve done something old, too, as old as time itself. Down is a place of challenge – there are secrets to be uncovered, battles to win, knowledge to be retrieved, and two worlds to save – and change, both mental and physical. The three questions that recur in Babylon 5 – Who are you? What do you want? Do you have anything worth living for? – are circumvented by Down, because it already knows the answers, even if you’re in denial.

At its best, portal fantasy offers us a narrative metaphor for seismic shifts in our cognitive landscape. Because our image is clearly reflected in the mirror, it can help us better decide if we like what we see. If we cross over to the Otherworld, we come back different people, if we come back at all. The portal is not a way out, but the way in.

Guest Post – Jacey Bedford on whether she writes SF or F?

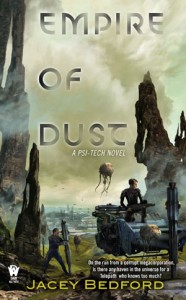

As I’ve mentioned previously, I’m very much enjoying Jacey Bedford’s Psi-Tech novels, namely Empire of Dust and Crossways, which are thoroughly good space-opera ticking all the boxes that first made me love SF while also thoroughly satisfying to me as a contemporary reader. So I was both startled and intrigued to learn that her new book, Winterwood, is a historical fantasy, set around 1800, with pirates and spies and mysterious otherworldly creatures all entangling Rossalinde Sumner in their machinations. You won’t be surprised to learn I invited Jacey to tell us all about that, and she has generously obliged.

SF or F? Trying to work out the differences and similarities.

With Winterwood, the first book of the Rowankind Series, on the brink of publication, Juliet asked me to write about transitioning between writing science fiction and fantasy. I sat down to think about it, but the more I worked on the differences between the two, the more similarities I came up with.

For starters, from the outside it does look as if I made a switch in genres, but it’s not quite the way it looks from the inside. My first two books to be published. Empire of Dust (2014) and Crossways (2015), are science fiction/space opera, but it’s a quirk of the publishing industry that they came out first. Winterwood, my historical fantasy, was actually the first book I sold to DAW, back in 2013, but it was part of a three book deal. DAW’s publishing schedule was such that there was a gap in the science fiction schedule before the fantasy one, so Empire of Dust ended up being published first. The order of writing, however, was Empire, Winterwood, and Crossways.

Confused? I don’t blame you.

Confused? I don’t blame you.

Let me backtrack. The road to publication is often slow and tortuous. Many of us who eventually make it have a drawer full of completed books before getting the magic offer from a publisher. These aren’t necessarily bad books or rejected ones, but ones that have not been on the right editor’s desk at the right time. The difference between a published writer and an unpublished one is often, simply, that the unpublished one gave up too soon. I started writing my first novel in the 1990s without any hope of finding a publisher, and with no knowledge of how to go about it, even if I’d been brave enough to try. That, however, was all about to change – mostly because of the internet. Once I got online in the mid 90s I connected with real writers via a usenet newsgroup called misc.writing, and learned all the basics about manuscript format and submission processes. (And yes, I’m still in touch with some of those very generous writers two decades later.) While all this was going on I finished a couple of novels and made my first short story sale.

The two early novels, at first glance, were second world fantasies, but the deeper I got into them the more I realised that they were actually set on a lost colony world. There are places where science fiction and fantasy cross over to such a degree that it’s hard to see where the boundary is. My lost colony world had telepathy but no magic. So thinking about it logically, how did that colony come to be lost? What put telepathic humans on to a planet and then kept them there, isolated from, and ignorant of, their origins?

That was the question that I started writing Empire of Dust to answer (though it may take all three Psi-Tech books to do it). Because the story involved planets, colonies and space-travel, I was suddenly writing science fiction. I don’t write hard, ideas-based SF. I’ve always been far more interested in how my characters’ minds work than what drives their rocketships, though I’ll always try to make the science sound plausible if I can.

Characterisation – that’s always the crux of the matter for me. Take interesting characters and put them into difficult situations and see what they do. It doesn’t actually matter whether they are in the past or the future, or even on a secondary world, what matters is that the characters grow and develop via the story to overcome problems and reach a satisfactory conclusion. Well, OK, the setting matters, but it’s not always the first thing that hits me. The setting and the detailed worldbuilding grows around the characters and weaves through the story, adding context and interest, and sometimes becoming a character in its own right.

So Empire of Dust, in a much earlier form, was finished in the late 90s and then began the rounds of publishers’ slushpiles. Remember what I said about persistence? Well, I’m dogged, but not always very pushy. Empire sat on one editor’s desk at a major publishing house for three years after the editor in question had said: ‘The first couple of chapters look interesting. I’ll read it after Worldcon.’ It took me three years to figure out I should withdraw it and send it somewhere else. Then the next publishing house it went to took another fifteen months. Those kind of timescales can eat up a decade very quickly. (I know one author who took to sending her languishing submissions a birthday cake after a year.)

In the meantime I kept on writing. It just so happened that the next three books were fantasies unrelated to each other: a retelling of the Tam Lin story aimed at a YA audience; a fairly racy fantasy set in a world not dissimilar to the Baltic countries in the mid 1600s, and a children’s novel about magic and ponies (not magic ponies). Why fantasy? I think I instinctively wanted to widen the scope of what I was doing to take in a wide variety of settings, however it was still mainly dictated by the characters.

If story and character are a universal constant, surely the difference between writing science fiction and fantasy is all down to worldbuilding. Right? Uh, well, maybe…. Science fiction can (to a certain extent) be fuelled by handwavium based on the accumulated reader-knowledge of how SF works. SF readers have an idea of how physics can be bent without being completely broken, whether you’re talking about the physics of Star Trek (warp-drives, photon torpedoes), or the hard SF of Andy Weir’s The Martian (which I love, by the way). When you write fantasy, you don’t have Einstein to fall back on. You have to work out how your fantasy world works from the ground up. If there’s magic, the magic system has to be logical and not contradictory (unless you build in a reason for the contradictions). If it’s set on a secondary world you might have strange creatures, races other than human, or even gods who act upon the world or the characters. Though, come to think of it, aliens, strange flora and fauna, and even ineffable beings are obviously common to science fiction as well. And when I said fantasy doesn’t have Einstein to fall back on, it does have the accumulated folklore of several millennia to point the way.

I think I’ve just talked myself round in a circle. So far, so similar.

So I started my next project, Winterwood, around 2008. By this time Empire of Dust had had three near misses with major publishers, but was still doing the rounds.

Winterwood almost wrote itself. I had the first scene very firmly in my mind – the deathbed scene – a bitter confrontation between Ross and her estranged mother. I wrote it to find out more about the characters and their situation. Ross hasn’t seen her mother for close to seven years since she eloped with Will Tremayne, but now her mother is dying. About halfway through the scene Ross’ mother asks (about Will): ‘Is he with you?’ Ross replies: ‘He’s always with me,’ and then follows it up with a thought in her internal narrative: That wasn’t a lie. Will showed up at the most unlikely times, sometimes as nothing more than a whisper on the wind. That was an Ah-ha! moment. I realised that Will was a ghost. Ross was already a young widow. That led me deeper into the story and gave me another character, Will’s ghost – a jealous spirit, not quite his former self, but Ross is clinging to him because he’s all she has left. That sets the scene nicely for when another man finally enters Ross’ life, but the romance is only part of the story. Ross inherits a half-brother she didn’t know about, and task she doesn’t want – an enormous task with huge consequences. There are a lot of choices to be made, and no easy way to tell which are the right ones. Ross has friends and enemies, some magical and some human, but sometimes it’s difficult to tell them apart. Even her friends might get her killed.

When that first scene came into my head, it could have been set in any place, any time. Parents and their children have been disagreeing and falling out for as long as there have been parents and children and, I’m sure, until we decide to bring up all our offspring in anonymous nurseries, it will continue well into the future. Ross took shape as I wrote, and I realised it was set in the past, or a version of it. In her first incarnation Ross was a pirate rather than a privateer, but I wasn’t sure what historical period to set the book in. The golden age of piracy was really in the 1600s, but I wanted to set this slightly later, so I decided that 1800 was a good time to play with. It’s a fascinating period in history with the Napoleonic Wars about to kick off in earnest, Mad King George on the British throne, the industrial revolution, the question of slavery and abolition, and the Age of Enlightenment. Of course I added a few twists, like magic, the rowankind and a big bad villain, who is actually the hero of his own story, though that doesn’t make him any less dangerous to Ross.

Historical fantasy is yet another subset of F & SF. If you’re writing in a specific historical period, you can make changes to incorporate your fantasy elements, adding magic for instance, or tweak one historical, point, but then you have to make sure that there’s enough solid historical background to make the rest of it feel authentic. You’re not necessarily looking for truth, but you are hoping for verisimilitude. I’m an amateur historian, not an academic one, but I did a lot of research: reading, museums, studying old maps and contemporary photos. I have several pinterest boards devoted to visual research, costume (male and female), ships, transport and everyday objects. Whenever I find something interesting I pin it for later consideration.

So where did we leave the publishing story? Oh, that’s right, Empire of Dust was doing the rounds of publishers’ slushpiles. While that was happening I submitted Winterwood to DAW and after about three months got that phone call that every unpublished author wants. Sheila Gilbert said: ‘I’d like to buy your book.’ One thing turned into another and before long I had a three book deal. As I said earlier, Sheila decided that Empire of Dust would be the first book out, even though it had been Winterwood that had initially grabbed her attention. Then she ordered a sequel to Empire, which was the book that became Crossways. If you want me to talk about writing a book to order, sometime, that would be another post altogether. Suffice it to say that Crossways came out in August 2015 and allowed me to take the stories of Cara and Ben to another level and move the setting from the colony planet to a huge, and vastly complex, space station, beautifully illustrated on the book’s cover by Stephan Martiniere.

So where did we leave the publishing story? Oh, that’s right, Empire of Dust was doing the rounds of publishers’ slushpiles. While that was happening I submitted Winterwood to DAW and after about three months got that phone call that every unpublished author wants. Sheila Gilbert said: ‘I’d like to buy your book.’ One thing turned into another and before long I had a three book deal. As I said earlier, Sheila decided that Empire of Dust would be the first book out, even though it had been Winterwood that had initially grabbed her attention. Then she ordered a sequel to Empire, which was the book that became Crossways. If you want me to talk about writing a book to order, sometime, that would be another post altogether. Suffice it to say that Crossways came out in August 2015 and allowed me to take the stories of Cara and Ben to another level and move the setting from the colony planet to a huge, and vastly complex, space station, beautifully illustrated on the book’s cover by Stephan Martiniere.

Getting a book from writer to store shelf is a multi layered process. There’s the writing and then the edit – which usually means some rewriting with additions. The once the final story has been accepted as finished it goes through copy-editing where clunky prose and spelling mistakes are smoothed over, and in my case, my British English is translated into American. Once the copy edits have been done then next part that I’m involved in is the page proofing, the final check after the book has been put into its finished form. This is the last chance to catch typos and brainos, but there’s no real opportunity to make big changes.

During the various editing processes there are gaps while your editor reads and considers, or the copy editor does his or her thing, so you tend to be working on other stuff while you’re waiting. The beginning of one book overlaps the editing process on the previous one and will in turn be at the editing and copy-editing stage when you’re just beginning to write the book after that. So, you see, it’s not like you have the luxury of working on one book at a time. The whole process is plaited together, fantasy and science fiction running alongside each other.

Winterwood comes out on Tuesday 2nd February. I’m currently writing Silverwolf, its sequel, which is due out late 2016 or early 2017. After that I’m contracted to write a third Psi-Tech novel (the aforementioned Nimbus), so it’s back to another space opera to follow on from Empire of Dust and Crossways. After that I’d like to write a third Rowankind novel. I already have ideas and there will be a few loose ends at the conclusion of Silverwolf, though, don’t worry, I never leave books on cliffhangers.

So the transition between science fiction and fantasy is not neatly delineated. It’s all mushed up together in both my writing timeline and in my brain. On the whole I just write stories set in different worlds. Some of them happen to have rocket ships, and others have magic, but all of them have characters who have adventures, relationships, and make choices, good and bad. I’m happy hopping between the future and the past, and I’m super-happy that my publisher has given me the opportunity to be an author who writes both SF and F.

You can keep current with all Jacey’s news over at her website.

P.S I’ve just finished reading Winterwood and can recommend it as highly as the Psi-Tech Novels.

Guest Post – Tricia Sullivan on World Building and the Kobyashi Maru

Tricia Sullivan has a new book out this week, Occupy Me, and I think it’s fair to say her award-winning, idea-driven SF is worlds away from my own style of epic fantasy fiction. And yet, as is the case with a good many writers whose work is nothing like mine, we have a good few things in common; the foundation for our friendship and mutual respect. One of those things is a background in tabletop and computer gaming and Tricia’s written a fascinating article examining the relationships between that style of world building and truly creative writing.

Once you’ve read it, I’ll be very surprised indeed if you’re not prompted to find out more about Tricia and her work – if you’re not already familiar with her books!

“Kobiyashi Maru

Whenever somebody says ‘worldbuilding’ I think of Gary Gygax straight away. I think of polyhedral dice, graph paper maps for dungeons, hex paper maps for outdoors. I think of the languages I tried to invent and all that other good, ooky stuff.

I was a first-generation D&D player. My brother bought it in a box in 1979. I was in fifth grade, same year I read Dragonsinger, and I remember being genuinely scared by the giant spiders and ghouls in the sample dungeon. There were hardly any modules back then, so if you gamed you really had no choice but to make it all up yourself. D&D was a great enabler of storytellers. Its codification, numeration and classification of every damn thing both encouraged worldbuilding—by providing scaffolding—and also inhibited it—because D&D turned reality into a Lego set.

Don’t get me wrong—I’m very fond of Lego, but you have to admit the results are always pretty…well…square. D&D was square like that, too. I hated how designing anything in it was the equivalent of filling out 40,000 pages of requisition forms, ticking boxes all the way.

When you are building worlds, sometimes you want Lego, but other times you want Play-doh. Sometimes you want to be able to bend it and squish it. In the pre-digital era it used to be possible to express things without having to first establish the rules and the codes. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that D&D was coming in at the same time as Apple and Atari—it was more flexible than writing code, but at heart the game was all about the rules. And taken to the limit, the rules of the world can become more important than the thing you are trying to do.

Fictional worldbuilding is like that, too. You want the story to take flight in the reader’s imagination, but you never want the reader to see the billions of robots running around behind the scenes pulling leavers and heaving things into position. You’ve got to convince the reader they are immersed. How do you do that? I reckon you have to play with what people already know about the world—but of course, most of us don’t know very much! It’s interesting to me that one of the least conventional writers I can think of, Diana Wynne Jones, nevertheless authored ‘The Rough Guide to Fantasyland’ as a plea for at least a little rigour. To work well, fantasy has to stand on the shoulders of reality.

But what does rigour even mean, these days? Culturally, we have a certain D&D-based shorthand when it comes to kingdoms, quests, character classes and expectations—all mainstreamed thanks to video games. These archetypes are pretty distorted and some of them are tired as hell, but whether the shorthand is played straight or torqued in some way, it’s pretty much embedded in the DNA of SFF across all the platforms that now deliver SFF content.

The shorthand can be a great facilitator. As a writer, it’s not hard to use a prefab world and tweak it a little for your own purposes. It doesn’t take a big deviation in initial conditions from the world as we know it to a world that seems strange and new. Once you open up the toolbox (of environment, economic systems, biological structure, culture, history, yadda yadda yadda) you have endless permutations at your disposal to experiment with ‘what if’ and to run simulations—alternative worlds to our own, if you will. This is the primary function of imaginative play. It is also very hard work.

But causal extrapolation isn’t the end game, at least not for me. In fact, it’s often a trap, a dead end, an unwinnable situation. No, the end game is imagination. The end game is magic.

Real magic—if I can indulge in the oxymoron—isn’t systemized. It’s outside our understanding, by definition. It comes out of flashes of insight, surprise, transformation. To make those kind of fireworks go off in someone’s mind is a very tricky business, and I’d argue that to make it happen as a writer, you need total control and this includes knowing when to lose control. When to let go of the wheel. A world you’ve built becomes its own organism, has its own mind, and to give it lift-off there’s a point where you throw out the rules, throw out what you think you know, and let the thing take you where it needs to go.

Gaming doesn’t teach this, and as far as I know it’s not in the Dungeon Master’s Guide, but I’ll bet artists know what I’m talking about because they build worlds, too—that’s what art is. Even as it’s using rules, art is a protest against the rules.

If you really want to fly, then just for a moment, get meta. Don’t accept the limitations you’re given. Reprogram the fucking computer that your world is running on. Beat the Kobiyashi Maru.

The dice and the graph paper will still be there when you come down.”

You can find out more about Tricia, her writing and this book in particular, over at her website

When’s the right time to write a story?

As is so often the way, a few things cropping up in rapid succession got me thinking. One was interviewing Brandon Sanderson at Fantasycon last month, when (among many other things) we talked about the way you need to wait until a story idea is ready to be written.

This was already in my mind after turning up the original proposal I sent to my then agent and editor, outlining the Aldabreshin Compass sequence. Or rather, not outlining nearly as much of it as I vaguely recalled.

And then of course, Sean Williams had written that very interesting guest blog post here on things he’s learned, taking the long view as he looks at his writing career thus far, for lessons to apply to his work yet to come.

So you can read my experience and conclusions on learning to let the seeds of a story ripen in full over on Sean’s blog.

Meantime, I’m aiming to get my Alien Artefacts short story written just as soon as I can carve out some time from VATMOSS stuff. Not to mention the ongoing ebook project.

Guest Post – “Death by a Thousand Shortcuts” according to Sean Williams

As well as getting out and about talking about things elsewhere on the Net, I’m inviting other authors to share their thoughts here to entertain you. This week, Sean Williams has obliged with a particularly interesting piece taking the long view of the writer’s life.

A funny thing happened on the way to finishing my first novel.

I realized that writing is hard.

Every writer has that epiphany. It’s important because without it we’re doomed never to improve. If writing a first novel seemed easy to you, then you’re either a flat-out genius or you weren’t paying attention. Hint: there are precious few people in the former category.

Saying that writing is hard is not to say that it can’t also be fun. It can also be all-consuming, therapeutic, any number of other things. But it’s tricky getting the words in the right order. Imagine lining up 80,000 dominoes so they’ll fall exactly the right way. (If you’d done that in the 70s, that would’ve earned you a world record.) Why should it be any different with words? Not to mention the fact that words come in all different shapes and sizes, and fall in so many different ways . . .

The good news is that, as with everything, you get better with practice. I learned this by writing a second novel, and a third. I sold my fifth, and I kept writing. By book ten or so I began to suspect that I had grasped the basic premise of the novel as a thing one spins out of nothing, as opposed to something one buys in a bookstore, fully formed. My books were being picked up by publishers, and they were even occasionally winning awards and appearing on bestseller lists. Practice was demonstrably making better.

And then, around book twenty, another funny thing happened.

It came upon me suddenly that, when writing, I wasn’t really thinking about stuff that had caused me great concern back when I was new. Sentence structure, dialogue, metaphors . . . all that stuff seemed to have vanished from my conscious process, leaving me feeling as though I was mechanically stringing words in a line. It didn’t feel hard anymore.

Fearing self-delusion (and the collapse of my career) I immediately stopped to read the ms over from the beginning, braced for the terrible news that I would have to find something else to do with the rest of my life. Interpretive dance, perhaps.

What I saw on the page amazed me.

Sentences were shaped, dialogue was natural, metaphors were not just present but effective . . . Where had all this come from? If I hadn’t written it, who had?

The answer is obvious in retrospect. My subconscious, honed by more than a decade of producing publishable material, was beavering away even when it felt as though the words were pouring forth without effort. Writerly chores had become instincts that I barely needed to think about anymore.

I had grown a writer-brain inside my ordinary brain. To get it working all I needed to do was give it a nudge like a clockwork toy and let it wobble across the page.

Having a writer-brain felt like a levelling-up gift from my former self. It was as though I’d finished an apprenticeship. Or built a supercharged motor. Now I could get into the driver’s seat and peel out.

It was around then that I started experimenting in new ways, doing things like having characters speak solely in the lyrics of British electro pioneer Gary Numan or trying to create my own religion Writing is supposed to be hard, I figured. Playing it safe is the art-killer.

And while this is absolutely true, I don’t think it’s true in the way I thought it was back then. Because another funny thing happened just recently, this time around my forty-third novel . . . something I’m still coming to terms with.

Aside: Let me just say that writing careers are like the words they’re made of, in that each is unique. There are lots of different trajectories across the creative landscape. I like to write lots of different kinds of things and I like to write quickly. It’s possible I would’ve written better if I’d written more slowly, but it’s equally possible I would’ve gotten bored and pursued that dance career. You’re not going to tell me that I’m a failure for churning out so many books just like I’m not going to tell you that you’re a failure for having fewer. Or more. Or whatever. You measure your successes and failures your way. You’re on your own journey. We’re waving as we go by, checking out each other’s scars.

I say this because, whether you’re a career writer who’s written forty books or four, you might one day go through a year like the one I’ve just had, where I sincerely felt as though I’d forgotten how to write novels. Not short stories, film scripts, or poems (I was never particularly good at the last). Just novels. And it wasn’t that I had suddenly lost the ability to string a sentence together or any of those basic skills. The writing-brain was still there. I had simply forgotten how to maintain it.

To go back to the car metaphor, it was as though I’d built a Lamborghini from scratch, but then done nothing but drive it around. I hadn’t tuned it. I hadn’t changed the oil or the tyres. I had relied on my subconscious to do the work without realizing that it was getting tired and I was getting lazy.

And eventually, after one lap too many, the engine light came on, a puff of black smoke coughed out the exhaust pipe, and everything juddered to a halt.

There’s nothing as startling as running headlong into a glass wall. It took me months to work up the courage to try again. In the meantime, I read a bunch of wonderful books and experimented with new forms, which might be the equivalent of getting back under the hood and replacing the spark plugs (I don’t know that much about cars, to be honest). I began to pay closer attention to what I was doing, and noting where mental shortcuts were causing problems I wasn’t seeing, because if the process of creation is subconscious, then sometimes our critical engagement with those creations is out of our conscious control. Which is bad. We can’t fix what we don’t understand.

Me and my writer-brain, I realized, we’re like an old married couple. We grew apart. That’s what happens when you take each other for granted. Every relationship requires nurturing, even your relationship with your art, and I forgot that, to my detriment.

When my writing-brain started up again, I found it to be just as capable as before . . . but different, which I guess is inevitable after a year of fallow time and introspection. In that frustrating time, I learned a lot about myself, about the kind of stories I like and the stories I want to tell.

Writing is hard. It takes effort and concentration. There’s no right way to do anything, only the way that works right now–which may never have worked before and might not ever work again.

But that’s not a disincentive. Not at all. Because if funny things didn’t keep happening to me along the way, my writing career might start looking a lot like work . . .

Sean’s new book, Hollow Girl is the conclusion to the Twinmaker trilogy, hailed as “mind-boggling” (Locus), “a philosophical marathon” (Kirkus), and “a gripping sci-fi story of friendship, identity + accidentally destroying the universe” (Amie Kaufman).

And just look at that cover art! (Click to see it full size)