Category: creative writing

The importance of thinking about ‘local values’ when you’re writing.

An American pal and her sister spent a few days here recently. A circuitous route to avoid some roadworks took us past Oxford Airport. Or, as I remarked, what locals still call Kidlington Airfield. I mean, the aircraft using it are twelve or twenty seaters.

‘Oh,’ says my pal, ‘big planes then.’ There was a ‘beg pardon?’ pause from me and a laugh from the car’s back seat. You see, these friends grew up in rural Alaska. As far as they’re concerned, a small plane is one where it’s just you and the pilot. Twelve seats? Luxury travel! Because normal is what you grow up with. As you can imagine, that led to a very interesting conversation.

And as is the way with authors, it’s started me thinking about the issues around local values when it comes to descriptive writing. I recall a conversation some time after Northern Storm was first published. In a bar, so after I’d given either a university or local SFF society talk. In that particular book, the magewoman Velindre spends time both in Einarinn’s frozen northlands, and later, in the tropical Aldabreshin Archipelago. The former is ‘bitterly cold’ and the latter is ‘oppressively hot’. I don’t recall what started the conversation but we were discussing exactly what those terms meant to us personally – and why I, as the writer, hadn’t included specific details to make it clear what a thermometer would say.

The first and most obvious answer is because I didn’t need to. With regard to ‘bitterly cold,’ the reader needs to know there’s snow on the ground and water is frozen. There was no plot or character related reason for me to indicate whether the temperature was minus three degrees or minus thirteen. Even a short paragraph going into more detail would have been wasted words and as far as I am concerned, every word in a book must count.

But it goes beyond that. My personal assessment of ‘bitterly cold’ is going to be very different to my Alaskan friend’s. Just as ‘oppressively hot’ means something entirely different to an author friend who lives in Hawai’i. At World Fantasy Con in San Diego a few years back, she was sitting in the full sunshine in a cardigan and considering getting a jacket while those of us just in from a UK October were grabbing all the shade we could find, sweltering in the most lightweight clothing we owned.

So going back to Northern Storm, adding more precise detail to either of those descriptions could well have been actively counterproductive. Specifying ‘oppressively hot’ in my own personal terms could very easily throw a reader used to a different climate right out of the story. Because their instinctive reaction would be ‘Wait, what? No, that’s not hot weather!’ And even something as apparently trivial as that could undermine the whole book for them. Because if a reader can’t believe in the background detail, how are they going to believe in the wizards and dragons?

On the other hand, you can turn this issue of local values to your writerly advantage, in the right place, for the right character. When I said minus three degrees or minus thirteen a few paragraphs back, I meant Celsius, because my local weather values are centigrade. When I come across temperatures given in Farenheit in US crime fiction, I always have to pause and do a quick mental conversion calculation. It disrupts the flow of my reading, so as far as I am concerned, that’s a bad thing.

But if I was a character in a book? If the author wanted to convey someone feeling unsettled and out of their usual place? Sure, that author could tell us ‘She felt unsettled by the unfamiliar numbers in the weather forecast’ but you could do so much more, and far more subtly, as a writer by showing the character’s incomprehension, having her look up how to do the conversion online, maybe being surprised by the result. It gets how cold in Minnesota in the winter?

It doesn’t just have to be about the weather. How about food? Anyone in the UK who travels to different cities and eats in Indian restaurants will know how much the chilli scale on menus varies. As I can attest from personal experience, what’s ‘medium hot’ in Bradford is a world away from ‘medium hot’ in Blandford Forum. There’s a lot a writer can do with that sort of thing.

It’s also worth checking your own local values/understanding against any historical or other background facts and resources you may be using. I was once attending a convention panel discussing the ancient world, when a genuinely baffled audience member sought clarification after a speaker discussed issues arising from the impossibility of telling slaves from free citizens in ancient Athens. But surely, the colour of their skin…? Because that questioner’s knowledge of slavery was entirely US-based and she was assuming central aspects of that were historically universal. Not so, by any means.

That’s perhaps an extreme example, but for instance, I’ve been caught out – though thankfully in a book’s planning phase, not in print – when assumptions I’ve made about growing and harvest seasons, based on my experience living in the UK, turned out to be nonsensical for the different climate and latitudes where I was setting some action.

So it really is worth taking a little time to consider what that well-known online phrase ‘Your Mileage May Vary’ could mean in relation to your writing, for readers and for characters.

Guest Post – Jacey Bedford on whether she writes SF or F?

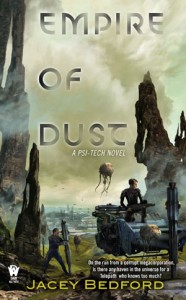

As I’ve mentioned previously, I’m very much enjoying Jacey Bedford’s Psi-Tech novels, namely Empire of Dust and Crossways, which are thoroughly good space-opera ticking all the boxes that first made me love SF while also thoroughly satisfying to me as a contemporary reader. So I was both startled and intrigued to learn that her new book, Winterwood, is a historical fantasy, set around 1800, with pirates and spies and mysterious otherworldly creatures all entangling Rossalinde Sumner in their machinations. You won’t be surprised to learn I invited Jacey to tell us all about that, and she has generously obliged.

SF or F? Trying to work out the differences and similarities.

With Winterwood, the first book of the Rowankind Series, on the brink of publication, Juliet asked me to write about transitioning between writing science fiction and fantasy. I sat down to think about it, but the more I worked on the differences between the two, the more similarities I came up with.

For starters, from the outside it does look as if I made a switch in genres, but it’s not quite the way it looks from the inside. My first two books to be published. Empire of Dust (2014) and Crossways (2015), are science fiction/space opera, but it’s a quirk of the publishing industry that they came out first. Winterwood, my historical fantasy, was actually the first book I sold to DAW, back in 2013, but it was part of a three book deal. DAW’s publishing schedule was such that there was a gap in the science fiction schedule before the fantasy one, so Empire of Dust ended up being published first. The order of writing, however, was Empire, Winterwood, and Crossways.

Confused? I don’t blame you.

Confused? I don’t blame you.

Let me backtrack. The road to publication is often slow and tortuous. Many of us who eventually make it have a drawer full of completed books before getting the magic offer from a publisher. These aren’t necessarily bad books or rejected ones, but ones that have not been on the right editor’s desk at the right time. The difference between a published writer and an unpublished one is often, simply, that the unpublished one gave up too soon. I started writing my first novel in the 1990s without any hope of finding a publisher, and with no knowledge of how to go about it, even if I’d been brave enough to try. That, however, was all about to change – mostly because of the internet. Once I got online in the mid 90s I connected with real writers via a usenet newsgroup called misc.writing, and learned all the basics about manuscript format and submission processes. (And yes, I’m still in touch with some of those very generous writers two decades later.) While all this was going on I finished a couple of novels and made my first short story sale.

The two early novels, at first glance, were second world fantasies, but the deeper I got into them the more I realised that they were actually set on a lost colony world. There are places where science fiction and fantasy cross over to such a degree that it’s hard to see where the boundary is. My lost colony world had telepathy but no magic. So thinking about it logically, how did that colony come to be lost? What put telepathic humans on to a planet and then kept them there, isolated from, and ignorant of, their origins?

That was the question that I started writing Empire of Dust to answer (though it may take all three Psi-Tech books to do it). Because the story involved planets, colonies and space-travel, I was suddenly writing science fiction. I don’t write hard, ideas-based SF. I’ve always been far more interested in how my characters’ minds work than what drives their rocketships, though I’ll always try to make the science sound plausible if I can.

Characterisation – that’s always the crux of the matter for me. Take interesting characters and put them into difficult situations and see what they do. It doesn’t actually matter whether they are in the past or the future, or even on a secondary world, what matters is that the characters grow and develop via the story to overcome problems and reach a satisfactory conclusion. Well, OK, the setting matters, but it’s not always the first thing that hits me. The setting and the detailed worldbuilding grows around the characters and weaves through the story, adding context and interest, and sometimes becoming a character in its own right.

So Empire of Dust, in a much earlier form, was finished in the late 90s and then began the rounds of publishers’ slushpiles. Remember what I said about persistence? Well, I’m dogged, but not always very pushy. Empire sat on one editor’s desk at a major publishing house for three years after the editor in question had said: ‘The first couple of chapters look interesting. I’ll read it after Worldcon.’ It took me three years to figure out I should withdraw it and send it somewhere else. Then the next publishing house it went to took another fifteen months. Those kind of timescales can eat up a decade very quickly. (I know one author who took to sending her languishing submissions a birthday cake after a year.)

In the meantime I kept on writing. It just so happened that the next three books were fantasies unrelated to each other: a retelling of the Tam Lin story aimed at a YA audience; a fairly racy fantasy set in a world not dissimilar to the Baltic countries in the mid 1600s, and a children’s novel about magic and ponies (not magic ponies). Why fantasy? I think I instinctively wanted to widen the scope of what I was doing to take in a wide variety of settings, however it was still mainly dictated by the characters.

If story and character are a universal constant, surely the difference between writing science fiction and fantasy is all down to worldbuilding. Right? Uh, well, maybe…. Science fiction can (to a certain extent) be fuelled by handwavium based on the accumulated reader-knowledge of how SF works. SF readers have an idea of how physics can be bent without being completely broken, whether you’re talking about the physics of Star Trek (warp-drives, photon torpedoes), or the hard SF of Andy Weir’s The Martian (which I love, by the way). When you write fantasy, you don’t have Einstein to fall back on. You have to work out how your fantasy world works from the ground up. If there’s magic, the magic system has to be logical and not contradictory (unless you build in a reason for the contradictions). If it’s set on a secondary world you might have strange creatures, races other than human, or even gods who act upon the world or the characters. Though, come to think of it, aliens, strange flora and fauna, and even ineffable beings are obviously common to science fiction as well. And when I said fantasy doesn’t have Einstein to fall back on, it does have the accumulated folklore of several millennia to point the way.

I think I’ve just talked myself round in a circle. So far, so similar.

So I started my next project, Winterwood, around 2008. By this time Empire of Dust had had three near misses with major publishers, but was still doing the rounds.

Winterwood almost wrote itself. I had the first scene very firmly in my mind – the deathbed scene – a bitter confrontation between Ross and her estranged mother. I wrote it to find out more about the characters and their situation. Ross hasn’t seen her mother for close to seven years since she eloped with Will Tremayne, but now her mother is dying. About halfway through the scene Ross’ mother asks (about Will): ‘Is he with you?’ Ross replies: ‘He’s always with me,’ and then follows it up with a thought in her internal narrative: That wasn’t a lie. Will showed up at the most unlikely times, sometimes as nothing more than a whisper on the wind. That was an Ah-ha! moment. I realised that Will was a ghost. Ross was already a young widow. That led me deeper into the story and gave me another character, Will’s ghost – a jealous spirit, not quite his former self, but Ross is clinging to him because he’s all she has left. That sets the scene nicely for when another man finally enters Ross’ life, but the romance is only part of the story. Ross inherits a half-brother she didn’t know about, and task she doesn’t want – an enormous task with huge consequences. There are a lot of choices to be made, and no easy way to tell which are the right ones. Ross has friends and enemies, some magical and some human, but sometimes it’s difficult to tell them apart. Even her friends might get her killed.

When that first scene came into my head, it could have been set in any place, any time. Parents and their children have been disagreeing and falling out for as long as there have been parents and children and, I’m sure, until we decide to bring up all our offspring in anonymous nurseries, it will continue well into the future. Ross took shape as I wrote, and I realised it was set in the past, or a version of it. In her first incarnation Ross was a pirate rather than a privateer, but I wasn’t sure what historical period to set the book in. The golden age of piracy was really in the 1600s, but I wanted to set this slightly later, so I decided that 1800 was a good time to play with. It’s a fascinating period in history with the Napoleonic Wars about to kick off in earnest, Mad King George on the British throne, the industrial revolution, the question of slavery and abolition, and the Age of Enlightenment. Of course I added a few twists, like magic, the rowankind and a big bad villain, who is actually the hero of his own story, though that doesn’t make him any less dangerous to Ross.

Historical fantasy is yet another subset of F & SF. If you’re writing in a specific historical period, you can make changes to incorporate your fantasy elements, adding magic for instance, or tweak one historical, point, but then you have to make sure that there’s enough solid historical background to make the rest of it feel authentic. You’re not necessarily looking for truth, but you are hoping for verisimilitude. I’m an amateur historian, not an academic one, but I did a lot of research: reading, museums, studying old maps and contemporary photos. I have several pinterest boards devoted to visual research, costume (male and female), ships, transport and everyday objects. Whenever I find something interesting I pin it for later consideration.

So where did we leave the publishing story? Oh, that’s right, Empire of Dust was doing the rounds of publishers’ slushpiles. While that was happening I submitted Winterwood to DAW and after about three months got that phone call that every unpublished author wants. Sheila Gilbert said: ‘I’d like to buy your book.’ One thing turned into another and before long I had a three book deal. As I said earlier, Sheila decided that Empire of Dust would be the first book out, even though it had been Winterwood that had initially grabbed her attention. Then she ordered a sequel to Empire, which was the book that became Crossways. If you want me to talk about writing a book to order, sometime, that would be another post altogether. Suffice it to say that Crossways came out in August 2015 and allowed me to take the stories of Cara and Ben to another level and move the setting from the colony planet to a huge, and vastly complex, space station, beautifully illustrated on the book’s cover by Stephan Martiniere.

So where did we leave the publishing story? Oh, that’s right, Empire of Dust was doing the rounds of publishers’ slushpiles. While that was happening I submitted Winterwood to DAW and after about three months got that phone call that every unpublished author wants. Sheila Gilbert said: ‘I’d like to buy your book.’ One thing turned into another and before long I had a three book deal. As I said earlier, Sheila decided that Empire of Dust would be the first book out, even though it had been Winterwood that had initially grabbed her attention. Then she ordered a sequel to Empire, which was the book that became Crossways. If you want me to talk about writing a book to order, sometime, that would be another post altogether. Suffice it to say that Crossways came out in August 2015 and allowed me to take the stories of Cara and Ben to another level and move the setting from the colony planet to a huge, and vastly complex, space station, beautifully illustrated on the book’s cover by Stephan Martiniere.

Getting a book from writer to store shelf is a multi layered process. There’s the writing and then the edit – which usually means some rewriting with additions. The once the final story has been accepted as finished it goes through copy-editing where clunky prose and spelling mistakes are smoothed over, and in my case, my British English is translated into American. Once the copy edits have been done then next part that I’m involved in is the page proofing, the final check after the book has been put into its finished form. This is the last chance to catch typos and brainos, but there’s no real opportunity to make big changes.

During the various editing processes there are gaps while your editor reads and considers, or the copy editor does his or her thing, so you tend to be working on other stuff while you’re waiting. The beginning of one book overlaps the editing process on the previous one and will in turn be at the editing and copy-editing stage when you’re just beginning to write the book after that. So, you see, it’s not like you have the luxury of working on one book at a time. The whole process is plaited together, fantasy and science fiction running alongside each other.

Winterwood comes out on Tuesday 2nd February. I’m currently writing Silverwolf, its sequel, which is due out late 2016 or early 2017. After that I’m contracted to write a third Psi-Tech novel (the aforementioned Nimbus), so it’s back to another space opera to follow on from Empire of Dust and Crossways. After that I’d like to write a third Rowankind novel. I already have ideas and there will be a few loose ends at the conclusion of Silverwolf, though, don’t worry, I never leave books on cliffhangers.

So the transition between science fiction and fantasy is not neatly delineated. It’s all mushed up together in both my writing timeline and in my brain. On the whole I just write stories set in different worlds. Some of them happen to have rocket ships, and others have magic, but all of them have characters who have adventures, relationships, and make choices, good and bad. I’m happy hopping between the future and the past, and I’m super-happy that my publisher has given me the opportunity to be an author who writes both SF and F.

You can keep current with all Jacey’s news over at her website.

P.S I’ve just finished reading Winterwood and can recommend it as highly as the Psi-Tech Novels.

Creative writing articles – the latest link & a new permanent webpage to round up the rest

I’ve had a couple of invitations recently to write guest articles on different aspects of creative writing. You can find the first of them here at the SciFi Fantasy Network where I outline how I learned vital lessons about getting feedback, thanks to NOT getting published twenty years ago.

So that’s the first thing. Head on over and read that and feel free to pop back and let me know what you think. Meantime, on to the second thing here.

Looking for inspiration for these posts, I asked folks what would interest them and got a fine range of responses. Though in some cases, I thought, ‘hang on, haven’t I already written about that topic?’

A little research soon indicated that well, yes, I might well have written such an article but those pieces are not necessarily straightforward to find, especially when I wrote them over a decade ago!

It struck me pretty forcefully that a round-up was in order. I soon discovered that I’ve had good many and varied things to say over the years, but rather than bludgeon you with an endlessly scrolling blog post, a separate list would be more wieldy.

So here’s a dedicated page on the site to make everyone’s life that bit easier.

There’s a good range of reading for you to browse and dip into at your leisure, in roughly reverse chronological order, which is to say, the most recent at the top, oldest at the bottom, and including guest pieces by me elsewhere.

Below that you’ll find links to guest posts from other writers that have appeared on this blog.

Enjoy!

Western Shore. Mapping the Aldabreshin Archipelago and beyond.

‘Where did this unforeseen enemy come from?’ That’s the central question in this third novel of the Aldabreshin Compass quartet. Swiftly followed by ‘how did they get here?’, ‘why did they come?’ and ‘why are they so brutal?’

Kheda and his allies, old and new, discover most of the answers as Western Shore unfolds but before I could write any of that, I had to work out all these things for myself. Not only deciding where these unknown invaders did come from but establishing what had changed to enable them to cross the vast western ocean, since they’d never been seen before. ‘Well, they just decided to,’ simply wasn’t an option, any more than ‘because they’re just evil,’ is ever a satisfactory answer to ‘what makes the bad guys so bad?’

At least I had a map of the Archipelago to start with. I’d learned my lesson after having to reverse engineer the original Einarinn map from accurately calculated travel details in the text and my (literally) back-of-an-envelope sketch not long before The Thief’s Gamble was published. Okay, my husband had to do the actual work – I was and remain thankful that he’s an engineer whose apprenticeship including training as a draughtsman. Incidentally, he’s the one who insisted the Einarinn maps have projection lines, when I explained I needed a map which I could put a ruler on anywhere to measure distances on the same scale. He naturally felt thoroughly vindicated when we got an enthusiastically appreciative letter from a Geography Ph.D student in Washington State, USA, for whom flat-earth fantasy maps were a personal bug bear. But I digress.

As you see from this far more extensive map, I had the upper half of the Archipelago mapped by the end of The Tales of Einarinn, so extending the island groups and chains southward was easy enough. But then I had to decide what lay out to the west. ‘Here be dragons’ might be literally true but I needed to know where and why, and crucially, why they were on the move for the first time in more than living memory.

Because ocean and atmospheric currents had changed somehow? That looked like a promising possibility so I went off to do some research, including but by no means limited to buying The National Geographic Atlas of the Oceans and doing detailed searches through my National Geographic Archive CD-Roms. I learned all sorts of useful facts about jet streams, thermohaline circulation, deep cold water flows, tectonic plates and undersea ridges, as well as weather patterns, and what causes trade winds, the doldrums and El Nino. All fascinating and all terms and systems it would be impossible to reference directly in an epic fantasy novel without ruining, well, the atmosphere. This is definitely a situation where the Iceberg Rule of Research applied. Only a tenth of this work shows above the surface, which is to say, appears in the final novel, but that couldn’t be there without the other ninety percent.

Now I had the key information which I could add to my map and integrate into the story. More than that, I was now seeing more ways in which wind and sea currents and the distribution of islands would affect travel and alliances within the Archipelago. This work was already influencing the course of the events I had planned for Eastern Tide. It ultimately contributed to The Hadrumal Crisis as well but that’s another story.

But all this work stayed on the papers on my desk. When the Aldabreshin Compass was published in paperback in the UK, we were all forced to agree that the scale and layout of the Archipelago meant reproducing the whole thing at that page size could only offer readers a scatter of uninformative dots. When Tor produced the US hardback, they had more room to work with and included a very handsome map but that could still only offer a section of the Archipelago, unable to show its relationship to the mainland.

So only a limited number of fans got to see even that much. And as with the admirable Einarinn maps in the Orbit paperbacks, the copyright for that specific depiction of my original material remains with the publisher, not with me.

Well, that was then and this is now. As those who’ve bought Southern Fire and Northern Storm already know, these new ebook editions include a map of the entire Archipelago and now I’m adding it to the website. This time I have my elder son to thank, who took on the not inconsiderable task of cleaning up the digital scan of my master paper copy, with all its creases and pencil scribbles, as well as collating all the other bits of information jotted on sections I’d enlarged and printed off separately to cover with more coloured arrows and notes. Finally he added his own bit of artistic flair, deciding it needed to look like something found in a Hadrumal wizard’s archive, maybe left by some ambitious cloud mage seeing just how far up he could take a scrying spell. I reckoned he’d earned the right to do that.

So is this it? Well, as you can see, there’s still an awful lot of this world still to be mapped – and we haven’t even found out what might be happening in those lands we can already see but haven’t yet visited…

Guest Post – Tricia Sullivan on World Building and the Kobyashi Maru

Tricia Sullivan has a new book out this week, Occupy Me, and I think it’s fair to say her award-winning, idea-driven SF is worlds away from my own style of epic fantasy fiction. And yet, as is the case with a good many writers whose work is nothing like mine, we have a good few things in common; the foundation for our friendship and mutual respect. One of those things is a background in tabletop and computer gaming and Tricia’s written a fascinating article examining the relationships between that style of world building and truly creative writing.

Once you’ve read it, I’ll be very surprised indeed if you’re not prompted to find out more about Tricia and her work – if you’re not already familiar with her books!

“Kobiyashi Maru

Whenever somebody says ‘worldbuilding’ I think of Gary Gygax straight away. I think of polyhedral dice, graph paper maps for dungeons, hex paper maps for outdoors. I think of the languages I tried to invent and all that other good, ooky stuff.

I was a first-generation D&D player. My brother bought it in a box in 1979. I was in fifth grade, same year I read Dragonsinger, and I remember being genuinely scared by the giant spiders and ghouls in the sample dungeon. There were hardly any modules back then, so if you gamed you really had no choice but to make it all up yourself. D&D was a great enabler of storytellers. Its codification, numeration and classification of every damn thing both encouraged worldbuilding—by providing scaffolding—and also inhibited it—because D&D turned reality into a Lego set.

Don’t get me wrong—I’m very fond of Lego, but you have to admit the results are always pretty…well…square. D&D was square like that, too. I hated how designing anything in it was the equivalent of filling out 40,000 pages of requisition forms, ticking boxes all the way.

When you are building worlds, sometimes you want Lego, but other times you want Play-doh. Sometimes you want to be able to bend it and squish it. In the pre-digital era it used to be possible to express things without having to first establish the rules and the codes. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that D&D was coming in at the same time as Apple and Atari—it was more flexible than writing code, but at heart the game was all about the rules. And taken to the limit, the rules of the world can become more important than the thing you are trying to do.

Fictional worldbuilding is like that, too. You want the story to take flight in the reader’s imagination, but you never want the reader to see the billions of robots running around behind the scenes pulling leavers and heaving things into position. You’ve got to convince the reader they are immersed. How do you do that? I reckon you have to play with what people already know about the world—but of course, most of us don’t know very much! It’s interesting to me that one of the least conventional writers I can think of, Diana Wynne Jones, nevertheless authored ‘The Rough Guide to Fantasyland’ as a plea for at least a little rigour. To work well, fantasy has to stand on the shoulders of reality.

But what does rigour even mean, these days? Culturally, we have a certain D&D-based shorthand when it comes to kingdoms, quests, character classes and expectations—all mainstreamed thanks to video games. These archetypes are pretty distorted and some of them are tired as hell, but whether the shorthand is played straight or torqued in some way, it’s pretty much embedded in the DNA of SFF across all the platforms that now deliver SFF content.

The shorthand can be a great facilitator. As a writer, it’s not hard to use a prefab world and tweak it a little for your own purposes. It doesn’t take a big deviation in initial conditions from the world as we know it to a world that seems strange and new. Once you open up the toolbox (of environment, economic systems, biological structure, culture, history, yadda yadda yadda) you have endless permutations at your disposal to experiment with ‘what if’ and to run simulations—alternative worlds to our own, if you will. This is the primary function of imaginative play. It is also very hard work.

But causal extrapolation isn’t the end game, at least not for me. In fact, it’s often a trap, a dead end, an unwinnable situation. No, the end game is imagination. The end game is magic.

Real magic—if I can indulge in the oxymoron—isn’t systemized. It’s outside our understanding, by definition. It comes out of flashes of insight, surprise, transformation. To make those kind of fireworks go off in someone’s mind is a very tricky business, and I’d argue that to make it happen as a writer, you need total control and this includes knowing when to lose control. When to let go of the wheel. A world you’ve built becomes its own organism, has its own mind, and to give it lift-off there’s a point where you throw out the rules, throw out what you think you know, and let the thing take you where it needs to go.

Gaming doesn’t teach this, and as far as I know it’s not in the Dungeon Master’s Guide, but I’ll bet artists know what I’m talking about because they build worlds, too—that’s what art is. Even as it’s using rules, art is a protest against the rules.

If you really want to fly, then just for a moment, get meta. Don’t accept the limitations you’re given. Reprogram the fucking computer that your world is running on. Beat the Kobiyashi Maru.

The dice and the graph paper will still be there when you come down.”

You can find out more about Tricia, her writing and this book in particular, over at her website

In which I’m interviewed at the Scififantasy Network

A brief post amid doing a whole lot of other stuff. I’ve been chatting to the SciFiFantasyNetwork folk and you can now read the interview here

Enjoy! While I continue doing the aforementioned whole lot of other stuff…

The Lays of Marie de France in relation to short stories and the history of epic fantasy fiction

As mentioned previously, this has been a year of writing short stories for me, so I’ve been thinking rather more about shorter form fiction than I would have done if I’d been focused on writing a novel.

So naturally I seized the chance to contribute to SF Signal’s Mind Meld on ‘What Makes the Perfect Short Story?’ There are a whole load of other excellent contributions by very fine writers, including a good number of recommendations for you to follow up – since, as many people have been noting over the past year or so, short form fiction is currently going from strength to strength as people are finding it very well suited to reading on smart phones and tablets etc, on their daily commute and in other snatches of downtime.

The thing is though, this is nothing new – and I don’t only mean we should celebrate the role of magazines and periodical publications, especially in creating popular genre fiction, from The Strand Magazine publishing the Sherlock Holmes stories through to Hugo Gernsback and the launch of Amazing Stories.

My pal Julia recently lent me this book; Lays of Marie de France and Others. According to the author biography Marie was, ‘Born circa 1140, probably in Normandy. Spent most of her life in England. Died circa 1190.’

Not much to go on there. Well, (published in 1966, so now rather dated), the book’s cover flap copy gives us a little more –

She wrote in the last quarter of the twelfth century in a dialect known as the Langue d’öil but she may have come from any part of Northern France between Lorraine and Anjou, she may have been a Norman or Channel Islander, an Anglo-Norman or Norman-Welsh. After all the academic debate of the last sixty years her identity remains as misty as ever. But this lady, who seems to have composed her tales for the very sophisticated court of King Henry II, was an admirable narrator, and the justness and fineness of her sentiment in all that concerns the delicacies of the human heart are also remarkable. A more excellent writer of romances it would be hard to find. It was something of a feat alone to have written a story about a werewolf neither horrific nor disgusting.

The werewolf story was the one Julia and I were discussing – and believe me, a retelling would easily find a place in any modern urban fantasy anthology – but obviously I read the others. I was struck time and again, how well they tick all the boxes for what we consider to be the merits and appeal of modern popular short fiction, once allowances are made for the archaic language and the fact they were meant to be recited aloud rather than silently read. Which shouldn’t really be a surprise, since these were the popular fiction of their day. Let’s not forget that taking the long view of humanity’s relationship with narrative fiction, the novel and private reading are both comparatively recent developments.

I’ve always been interested in looking for the origins of fantasy fiction beyond the founding fathers who are usually cited. And yes, I use that term advisedly because so often it’s the female writers who have historically been ignored or dismissed for writing ‘women’s stuff’. That’s not in the least to disparage those male writers. Anyone looking for the origins of epic fantasy should assuredly go back to Beowulf, and to The Song of Roland, The Arthurian Cycle and all the rest.

But as this book makes so very clear, that’s by no means the whole story. Marie’s tales are full of action, treachery, tragedy, love, betrayal, magic and high heroics by men and women alike. Everything that keen readers are looking for in the best of modern epic fantasy writing – long and short. My understanding of the history of our genre becomes so much richer and more complex when I come across authors like her.

Here Be Dragons! Northern Storm’s new cover and associated thoughts

As you can see from the second of Ben Baldwin’s superb new covers for the Aldabreshin Compass series, this book has dragons! Big dragons. Dangerous dragons. As those who’ve already read The Thief’s Gamble can tell you, dragons in Einarinn can be truly devastating. And for those who’ve read The Thief’s Gamble and still have a whole load of unanswered questions about dragons in this world, rest assured you will find answers in this book. Some answers, anyway.

Click to see more detail

Dragons really are the archetypal epic fantasy monster. They feature in some of my very favourite books and series, as far back as I can recall. Was Smaug the first one I encountered? Smaug the Terrible, as proved by his merciless destruction of Lake Town, for all that he amused himself chatting to Bilbo beforehand. Or was it the Ice Dragon, Groliffe, in the Saga of Noggin the Nog? He’s Honorary Treasurer of the Dragons’ Friendly Society, you know. So dragons that communicate and co-operate were among my earliest childhood encounters as well.

That duality’s been there through my subsequent fantasy reading. Anne McCaffrey’s dragons on Pern; mighty beasts yet telepathic and empathetic. On the other hand, the massive, murderous creatures of Melanie Rawn’s Dragon Prince and subsequent books. The devastating dragon out to destroy Ankh Morpork in Terry Pratchett’s Guards! Guards!, alongside the pathetic swamp dragons of Lady Sybil’s Sunshine Sanctuary. Naomi Novik’s Temeraire series has any number of breeds of dragons, ranging from the brutish and violent to the intelligent and cultured – and just as many different ways for humans to interact with them. Dragons in the Harry Potter universe on the other hand, all seem to be terrifying and lethal, whatever their breed. Robin Hobb’s dragons will co-operate with humans as long as doing so suits their own purposes, or just their current whim, but any ‘keeper’ who thinks they’re in charge is likely to get a surprise. Morkeleb the Black offers Jenny Waynest untold gifts in Barbara Hambly’s Dragonsbane, but at what cost? We’re still waiting to see which side of the scales George RR Martin’s dragons will come down on, in A Song of Ice and Fire, but Daenerys Targaryen really had better keep her wits about her, don’t you think?

What about the myths that spawned all these fantasy beasts? Manifestations of the Universal Monster Template? I’ve been reading about them in books of folklore for just as long as I’ve been reading fantasy fiction. Not only the tales of Fafnir and Siegfried and such which inspired Tolkien and CS Lewis in varying ways, or the umpteen variations on St George’s story. Every English county seems to have its own local subspecies of dragon – The Lambton Worm (County Durham), The Mordiford Wyvern (Herefordshire), The Wantley Dragon (Yorkshire), to name but a few. The iconic red dragon of Wales, intertwined with the myth of Merlin and Arthur, is only one Celtic dragon myth, alongside the Dundee dragon, the Oilliphéist in Ireland fleeing St Patrick, and many more. Towns and villages right across Europe have tales of similar local beasts, usually spreading blight and destruction, with an appetite for young maidens. All so very different to ethereal oriental dragons with their ties to nature and the elements.

It sometimes seems a wonder that any fantasy author would write about anything else. I’ve only mentioned a few of the best known books on my shelves here, so feel free to flag up your own favourite books with dragons in comments. Fellow authors, by all means offer a brief introduction to your own take on the beasts.

What does using such an iconic monster mean for a fantasy author? Well, as with so many of these archetypal genre elements, the challenge is staying true to the core tradition while still finding something at least a little new and different to bring to the mythology. Above all else, as a reader, I find it’s essential for the beast have a convincing role within a fantasy world and an integral reason for its presence in the story. Not just being shoehorned in because someone once said a book with a dragon on the front sells more copies…

So what’s this particular dragon’s role in Northern Storm? You’ll have to read the book to find out, and all being well, the ebook edition will be rolled out across the various sellers over the next week or so. Keep an eye out for updates.

Work in progress and the value of constructive criticism

I’m currently revising a piece of short fiction in the light of a test reader sending a draft back with numerous comments on bits that aren’t as clear as they might be, things that seem clunky etc.

I’m not complaining in the least. Not even hinting that this is a hardship. Quite the contrary. I’m feeling a whole new rush of enthusiasm for this story now that I’ve got a fresh perspective on it, thanks to someone else’s eyes.

Especially since, to quote the accompanying email from the test reader “I’ve been setting the comb’s teeth quite fine.”

Yes, that’s exactly what I wanted. Exactly what this piece of work needed.

When people ask for writing advice, I’m inclined to reply with the qualifier, ‘well, this works for me…’ because no two writers I know work in exactly the same way and some things which work for my favourite authors would never suit my writing in a thousand years.

But if there’s one universal rule for writers, this is probably it. No matter who you are, no matter how long you have been at this game. Get feedback. No piece of work is so good that constructive criticism can’t make it better.

What’s the story? Well, do you recall many months ago, I was wondering whatever became of the young Daish warrior who fell off a battlement to be lost in the night’s shadows below…?

Right, back to it.

When’s the right time to write a story?

As is so often the way, a few things cropping up in rapid succession got me thinking. One was interviewing Brandon Sanderson at Fantasycon last month, when (among many other things) we talked about the way you need to wait until a story idea is ready to be written.

This was already in my mind after turning up the original proposal I sent to my then agent and editor, outlining the Aldabreshin Compass sequence. Or rather, not outlining nearly as much of it as I vaguely recalled.

And then of course, Sean Williams had written that very interesting guest blog post here on things he’s learned, taking the long view as he looks at his writing career thus far, for lessons to apply to his work yet to come.

So you can read my experience and conclusions on learning to let the seeds of a story ripen in full over on Sean’s blog.

Meantime, I’m aiming to get my Alien Artefacts short story written just as soon as I can carve out some time from VATMOSS stuff. Not to mention the ongoing ebook project.