Category: creative writing

A short(ish) post about short stories

Today sees Different Times and Other Places, my retrospective short fiction collection, published by Newcon Press. This is the latest in their Polestars series showcasing writers working across speculative fiction – who happen to be women. Selecting these stories has offered me insights into my development as a writer, as well as highlighting inspirations which I realise go back to my earliest reading. It has also given me the opportunity to share two completely new, previously unpublished stories. The Green Man’s Guest sees an unexpected encounter for Dan Mackmain in an arboretum, while A Stitch in Time Saves One explores an epic fantasy possibility that occurred to me and was simply too good not to use somewhere.

The only downside of putting this collection together – if I can even call it that – is I find I want to write more and longer stories about the people and places I have revisited. My natural writing length is the novel. Writing short stories is a skill I have consciously learned. It’s a distinctly different narrative form which I have come to appreciate, not least by reading the work of other authors who do this supremely well. Writing really good, effective short fiction absolutely isn’t simply a case of fitting a story into the required word count.

My first novel, The Thief’s Gamble, was an epic fantasy, a genre I still read and enjoy. I often come across potential inspirations for fresh ways of looking at magic, and of reflecting on our own lives using the magic mirror of a previously unimagined secondary world. These days, short stories allow me to explore these ideas in between writing my ongoing Green Man series of contemporary fantasy novels. And since a short story asks far less of a reader’s time, they are an excellent way to offer an introduction to my style and perspective as an author.

I don’t ever want to become complacent as a writer, so I continually strive to hone my skills. The best way to improve your abilities in any craft is to tackle new tests. That’s something else I get from short fiction. Writing for a themed anthology is an intriguing creative challenge as I look for an angle that no one else has seen. Then I get to read everyone else’s stories, and see the other possibilities they found. In Fight Like A Girl Volume 2, from Wizard’s Tower Press, it’s great to see so many authors from the first volume returning, as well as the contributions from other writers joining us. It’s very rewarding to see readers enjoying the breadth of perspectives this anthology offers.

Shared-world writing asks similar and also different questions of an author, as a group of writers work together to find the balance between individuality and collaboration that creates a coherent setting which becomes more than the sum of its parts. I contributed the story ‘Unseen Hands’ to the Ampyrium anthology from ZNB in the summer, working with and alongside a great roster of writers to build this new and original milieu.

February 2025 will see the publication of the Lincolnshire Folk Tales Reimagined anthology. This was a different writing challenge yet again. The team behind the ‘Lincolnshire Folk Tales: Origins, Legacies, Connections, Futures’ project at Nottingham Trent University are putting together a programme of launch events, which will include readings, Q&A and more, to promote interest and awareness of the origins and influences of this storytelling heritage. Check this page for the dates and places for events – you’ll need to scroll down for the newest additions.

And now? I’ll get back to working on a new, full-length project that I’m developing, alongside Dan’s next adventure…

What sparked The Green Man’s War?

The seventh instalment of Dan Mackmain’s adventures makes this the longest continuous sequence of novels that I’ve written. Okay, I actually reached that point with the last book, The Green Man’s Quarry but I’ve only just thought about this. The Tales of Einarinn came to a natural pause after five volumes. The subsequent books in the World of Einarinn timeline were a series of four novels, followed by two trilogies. With each of those sequences, I was determined not to rewrite a story I’d already told. Shifting focus to a different part of that fantasy world with a new cast of characters was a key part of ensuring that.

So how can I keep writing the Green Man books without repeating myself? It turns out elements embedded in these stories from the start are very helpful. I decided Dan’s life would be grounded in everyday reality. Writing epic fantasy novels showed me how a solid foundation makes the magical far more believable. With these books, that means a year or so between each story sees a year or so pass in Dan’s life. His relationships develop and his priorities change. That makes new demands on him and I can find new ways to threaten him.

These books are rooted in British folklore. This is a vast and varied resource. The more I read, the more I find to spur my imagination. I don’t necessarily find complete stories. Most local legends are single incidents, often tied a particular landscape feature or an old building. A lot of these stories are very similar, even when they’re set hundreds of miles apart. None of this is a problem. As I read these variations, I can use common threads to weave stories into the underlying mythology that’s evolving through this series. Where I find contradictions and exceptions, those can remind the reader not to take anything for granted. Where mentions of a monster are little more than fragments, I can devise something that’s both familiar and wholly new.

Then there’s the catalyst. The creative process that has emerged for these books is very different to my approach to writing an epic fantasy novel or a historical murder mystery. I plan those in detail from the start, and I tailor my research to the needs of the plot I’ve already worked out. Each Green Man book starts with me gathering assorted, apparently unrelated ideas from my folklore reading, from places I visit, from conversations with like-minded friends. I make note of news stories about rural life and concerns which will affect Dan and his friends. At that stage, I genuinely have no idea what the next book will be about.

Then I will come across something that suggests a way to tie these ideas together. Once I have that catalyst, the story starts to take shape. Its internal momentum shows me where and when to draw the next element in. Now my research is about finding the people and resources to tell me things I had no idea I would need to know. I will be well into writing the novel before I see the ending come into focus ahead. I would never have imagined I would be working this way, but the experience is as exciting as it has been unexpected.

So what was the catalyst for The Green Man’s War? When we were visiting Burford one day last winter, my husband saw a small bronze statue of three dancing hares in a jeweller’s shop window. Regular readers will understand why that caught his eye. We went in to buy it, only to discover the shop door should have been locked and the ‘Closed’ sign put up. A distracted member of staff had followed the usual routine on auto-pilot. The manager and staff were actually in the shop that morning to compile an insurance claim after being robbed the week before. A gang of men armed with hammers and knives had ambushed the keyholder outside, forced their way in, and stripped the shelves and display cases bare. The nice people in the shop were happy to sell us the little statue, once they had told us all about it.

That got me thinking. What would Dan do, faced with that situation? Why might something like that happen to him? I’d read a few myths that mentioned jewellery. Ideas started coming together…

Guest Post – Andrew Knighton on characters’ occupations.

I’ve shared in thoughtful panel discussions with Andrew Knighton at conventions, as well as more informal conversations. I am very pleased to share his article on the relationships between a character’s job of work and various aspects of a story.

Work is a fundamental part of life. It can provide purpose, frustrations, and a roof over your head. In a capitalist society, it’s the thing that most clearly defines your place in society.

Because of that, jobs can bring fictional characters to life in novel and fascinating ways. Not so much the common protagonist jobs, the warriors and police officers who power so many stories, but the unexpected choices, the jobs that are unusual for fictional protagonists even if they’re common in the real world.

Working the Story

Work as Character

A character’s job can tell you a lot about who they are at heart.

Take Ten Low, Stark Holborn’s frontier combat medic. She’s a wounded character in a wounded world, trying to patch people together as they get shot and stabbed and flung around. She’s clearly chosen this role to put some distance between her and who she was before, for reasons that become clear as the story unfolds. No one’s paying her to heal, but it’s definitely her job.

Charlie Mason, the protagonist of Neil Williamson’s Charlie Says, is a standup comic whose performances express his own insecurities, his fears, and the changes he’s gone through over the years. His profession becomes a hook the whole character hangs off, and with it the themes of the story. The standup comic as stand-in for modern Britain, defensive and abrasive, caught between the instincts to mock himself or to cruelly attack others.

That can extend to a group of characters. In N. K. Jemisin’s The City We Became, the avatar of the Bronx works at an arts centre, an outsider and creative; Brooklyn is a rapper turned politician, furiously battling the system; while Padmini, the avatar of Queens, is a logically-minded graduate student working in mathematics. Their professional roles reflect their personalities which in turn reflect the places they embody. Their jobs root them in geography and society, highlighting the connections of modern urban life and specifically of New York.

Work as Story

While any job can provide a window into a character’s heart, others more directly affect the story.

Dan Mackmain, the protagonist of Juliet E. McKenna’s Green Man series, is a man whose career reflects his character. He’s a carpenter and handyman who makes carved wooden objects, someone who’s practical and connected to the land, creative yet down-to-earth. His connection to the wood and world is what draws him into supernatural danger, but it also provides the pragmatic, worldly skills that let him survive otherworldly threats. It’s a hook for adventure and a tool to survive it.

That path from a character’s job to the challenges they’re going to face can be more direct. Ned Beauman’s Venomous Lumpsucker features a pair of protagonists who work in different specialist fields, one an animal scientist and the other an investment executive. Their perspectives let the story explore economic and environmental systems without drowning readers in textbook explanations or political diatribes, while the investor’s deals in a fictional commodity called “extinction credits” embodies economic structures gone wrong. Their shared knowledge gives the characters both the tools and the motive to go crack the systems of the world open, angles from which to see society and to shape it.

Work as Inspiration

Sometimes the job is the whole reason a story exists.

That category is where my new novel, The Executioner’s Blade, fits in. Inspired by Joel F. Harrington’s history book The Faithful Executioner, I started thinking about what the life of an executioner would be like and who would take on a job like that. It’s a job that’s been central to the functioning of many justice systems, but that’s viewed with fear and suspicion. A killer of killers, wielding violence to deter violent acts, living in tension with societies that want them to do the work but don’t want to know them afterwards.

I became fascinated with what sort of person would do that. Someone interested in justice. Someone who was happy to be shunned. Someone comfortable shedding blood. Preferably someone with the skills and experience to kill quickly and cleanly. Maybe someone living in tension with herself.

Inevitably, I thought about problems with capital punishment, not least the fact that miscarriages of justice happen. Sometimes the wrong person gets punished, and when the punishment is execution there’s no coming back from that. How would it feel for an executioner to learn that she’d killed an innocent person, that she’d been used to perpetrate a further injustice and cover the murderers trail? It felt like a good motive for a story, a character wanting to put right a wrong she’d unwittingly done, a murder mystery in which the killer is also the investigator.

The job became the story.

Collected Work

If there’s one book that shows how much you can do with a single profession, it’s Steve Toase’s Under My Skin, a collection of archaeological horror.

Through ten different stories, Toase shows how the same job can take a person, and an author, in very different directions. Characters range from the obsessive to the world-weary, the idealistic to the cynical. Their work includes digging holes, plotting maps, identifying finds, and theorising on what they’ve found. We see the giddy excitement of discovery and the repetitive tedium of paperwork. We meet characters fascinated by the work and others worn down by it.

The stories also find different ways to make the archaeological fantastical and unnerving. It could be something uncanny found in the ground, a colleague becoming increasingly strange thanks to his discoveries, or a survey of a town where the houses themselves become horrifying. In one case, archaeology becomes a profession for travelling to and interacting with another realm.

The same job, presented in ten very different ways.

And All the Rest…

Toase’s book left me thinking there should be more stories about archaeologists, because there’s so much potential in what they do. But maybe that’s true of any profession if you dig into it deeply enough or even sprinkle it with the twisting magic of genre fiction. We could be reading about Medusa’s hairdresser, about a takeout chef on an intergalactic highway, about stable hands cleaning out the manticore pens. There are books out there about magical bakers and the fire fighters in a world of dragons, but we could have so much more, a chance to see the fascinating characters that different careers can create.

#

Andrew Knighton’s new novel, The Executioner’s Blade, is out from Northodox Press on 28 November. You can find him at andrewknighton.com.

An interim update before I fly off to Sweden

I had an excellent time at Fantasycon in Chester, and an excellent time at Bristolcon, which is where you would expect it to be held. Having spent the last two days clearing the decks of work stuff, today will be getting everything ready for our trip to Sweden tomorrow. I’ll be one of the Guests of Honour at Fantastika 2024, this year’s Swecon, over the weekend. After that, husband and I are having a week’s holiday in Stockholm. (Burglars please note, Resident Son is taking vacation days while we are away to have his own holiday at home.) This will be our first break in what has been a challenging year for a range of reasons. I’m looking forward to coming home refreshed to work on a couple of things at a more relaxed pace than the past six months have allowed.

I’m also encouraged by what’s been a recurring theme in panel discussions, namely the importance of writers examining and discussing the origins of themes and archetypes they’re using. An important reason for this is to avoid perpetuating outdated and even harmful subtexts and ideas. More than that, writers are seeing the wide range of opportunities to be found in identifying the stories not being told, by looking at variations on legends, old and new, which don’t centre the most frequently-used characters and story structures. I feel this is excellent for the SF&F genre.

Enthusiasm at these conventions for the forthcoming new anthology Fight Like A Girl Volume 2 (Amazon pre-orders here) is very rewarding, as is people’s eagerness to read The Green Man’s War (Amazon pre-orders here), which will be published on 15th November,. For comprehensive lists of non-Amazon buying links check out the Wizard’s Tower Press pages for Fight Like A Girl Vol.2 and for The Green Man’s War.

Something I’ve found very entertaining is seeing readers (who tagged me in) discussing their responses to the Green Man series protagonist Dan Mackmain, as a character and as a ‘real person’. The consensus seems to be affection blended with intermittent exasperation, as expressed in splendid fashion here.

“Daniel. Sweetie. That’s gonna bite you in the ass later. Daniel. No. Please think this through.”

I’ve had some intriguing conversations about Dan in person as well. All of this encourages me to continue writing his story. It’ll be interesting to see where delving into my folklore To Be Read stack takes him next.

The way Dan’s occupation is interwoven with his personality, and influences his actions ,leads me very nicely into the guest post following this. Andrew Knighton has been reflecting on ways in which a fictional character’s work can colour and shape a story. I am very much looking forward to reading Andrew’s new novel, The Executioner’s Blade, when I get home from our travels.

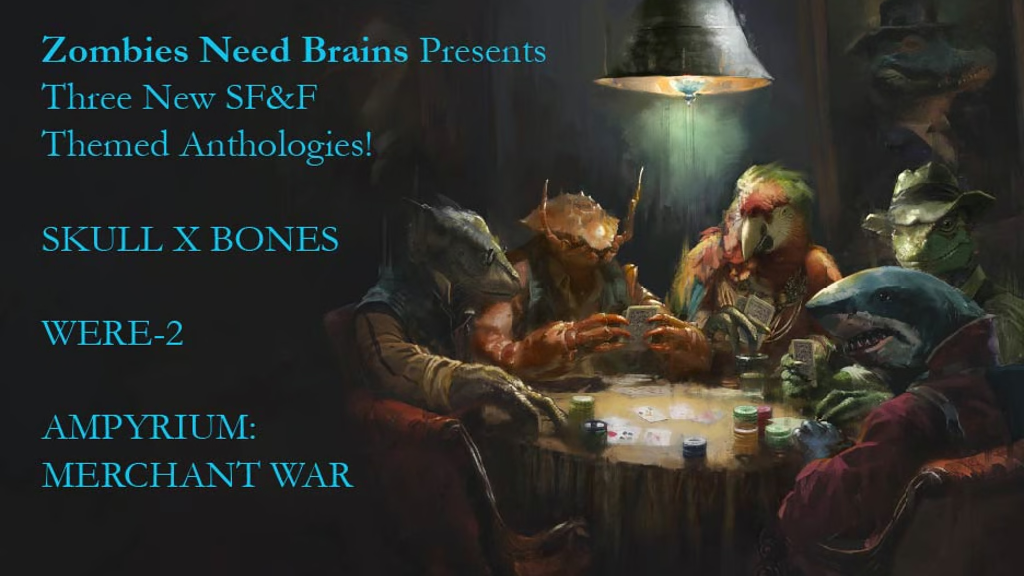

It’s ZNB Kickstarter time! Support great stories and an open call for submissions

I mentioned my Ampyrium short story a while ago. I’m thrilled to say I’ll be returning to this fascinating shared world with one of this year’s ZNB anthology projects.

As regular readers will know, each year for over a decade now, this splendid US small press produces collections of original (no reprint) short stories (around 6,000 words), funded by Kickstarter. You’ll find great reading from a mix of established SF&F authors and new voices found through their open submissions call, announced once the Kickstarter is funded. Editorial standards are rigorous, and ZNB is a SFWA-qualifying market, paying professional rates.

This year’s projects are as follows:

WERE-2

It’s the night of the full moon, and in the back alleys in the dead of night, were-creatures might see you as prey. A were-raven? Were-squirrel? Were-octopus? You won’t know until you hear that rustle of feathers next to your ear or smell the brine of the sea. Editors S.C. Butler & Joshua Palmatier are looking for creative were-creature tales with only one rule: No werewolves allowed!

Anchor authors include: Randee Dawn, Auston Habershaw, Gini Koch, Gail Z. Martin & Larry N. Martin, Harry Turtledove, Tim Waggoner, and Jean Marie Ward.

SKULL X BONES

Pirates have enchanted and haunted readers for generations, from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island to the ill-fated Firefly to Black Sails and Our Flag Means Death! From swashbucklers to scruffy-looking nerfherders, David B. Coe & Joshua Palmatier want writers to come up with their best science fiction or fantasy pirates, whether they’re plundering the golden age of sail on this or some other world, or leaving the blue behind on a spaceship heading into the black.

Anchor authors include: R.S. Belcher, Alex Bledsoe, Jennifer Brozek, C.C. Finlay, Violette Malan, Misty Massey, and Alan Smale.

AMPYRIUM: MERCHANT WAR

The city of Ampyrium is bustling with trade…in the midst of a Merchant War! It is the hub for eight portals to other worlds, where goods and more change hands both above and beneath the table. Does any business escape the Eyes of the enigmatic Magnum who first created this city of magic and mayhem, saintliness and sin? What nefarious plans are now afoot?

I’ll be writing alongside my fellow anchor authors Patricia Bray, S.C. Butler, David B. Coe, Esther M. Friesner, Juliet E. McKenna, Jason Palmatier, and Joshua Palmatier – who is also our highly esteemed editor.

The Kickstarter runs until 15th September 2024 and offers bonus rewards and incentives at all levels.

An interim update and a writing ‘first’

A quick note to say that I had an excellent time at Worldcon, and I plan to write more fully about that soon. Just at the moment, I am head down, working flat out, and resolutely maintaining my focus on the work in progress.

That focus was interrupted yesterday by an unexpected and rather startling ‘first’ in my 25+ years as an author. So unexpected that I’m pausing briefly to share it.

In the months between first drafting the outline of this book, and finalising the end of the draft [REDACTED] has become a tightly controlled substance in the UK. Previously widely available [REDACTED] is now so tightly controlled that online references I had bookmarked have disappeared without any explanation. I only found out what was going on when considerable lateral thinking on search terms brought me to a model railway club’s website. The model railway club secretary highlighted the relevant new law, along with the substantial penalties which now apply for possessing [REDACTED] without the relevant government licence which requires an application and payment, and expires after three years.

Yes, I know you are now eager to know what [REDACTED] is, and I will cover all this in the book, but having read the reasons for this new law, I’m not going to discuss it online on social media. Seriously.

This writing life offers endless surprises.

Thinking about escapism … back in 2006

After writing my previous post, another recollection has been prodding me. I’d had a few things to say about escapism. A fair while ago. I must written that up for the blog, surely? It’s a challenge thrown down in front of fantasy writers often enough.

No… I couldn’t find that on the blog anywhere. So what was I thinking of? Checking the archive on my hard drive, I found my notes for the BFS Fantasycon in 2006. As a Guest of Honour, I was expected to say ‘a few words’ after the banquet, along with the other GoHs Neil Gaiman, Raymond Feist, Ramsey Campbell and Clive Barker. (Talk about ‘one of these things is not like the other things’…)

So here you go – bearing in mind what we actually say when speaking from notes is never precisely what we’ve got written down. Regardless, I stand by these thoughts here in 2024.

“I’ve been checking diaries with friends recently, trying to find weekends when we’re all free to meet up, and when this weekend’s come up, I’ve explained I’m going to be away, here at FantasyCon. And they’ve said, with varying degrees of bafflement or envy, ‘so you’ll be escaping for a few days.’

And I am. I’m escaping running the house and the shopping and the laundry situation and organising my sons so they have their sports kit and their swimming gear and ingredients for food tech on the right days so I’m not expected to produce pizza ingredients at 7.30 in the morning and they’re up to date with their homework and all that kind of thing.

But it’s not what I’m escaping from that’s important, it’s what I’m escaping to.

This weekend, on panels, in the bar, in the lifts, I’ve had conversations about about children’s fantasy literature and how books influence a child’s moral and mental development. We’ve been talking about crime fiction and its relationship to fantasy and that takes us into questions of motivation and morality. I’ve talked politics and current affairs and this is important stuff. So this weekend I’ve escaped to a space where I can look at wider horizons for a while and I’ll go home mentally refreshed and feeling the better for it.

I’ve escaped my own work. I’ve escaped the clutter in the study. I’ve escaped the shelf of science fiction and fantasy books that I feel I really must read. And the shelf under that of non-fiction waiting to be read.

I’ve escaped to a place where I’ve been meeting other writers and hearing about how they work and the ideas and impulses that drive them, that inform their fiction. This weekend, I’ve had a revelation. I don’t do horror. I just don’t get it. Yesterday Raymond Feist was talking about horror being a roller coaster ride. That explains it. I can’t stand roller coasters. So I’ll go home with a far clearer perspective and my writing will be the better for it.

I’ve escaped to a place where I’ll get support and new arguments and new reasons to convince people that heroic fantasy is no more about patriarchal, misogynistic heroes offering a consoling pat on the head, any more than horror is just some pervy hackfest with blood, slime and tentacles or hard SF is merely the technobabbling rapture of the nerds. So I’m certainly not escaping to anywhere where I just stick my brain in neutral.

I’ve escaped to somewhere where I’ll have my own prejudices challenged. Last year Simon Green was talking about The Haunting of Hill House as a classic in the horror genre. As I say, I don’t do horror. But Simon was talking about it and then I heard it mentioned in a talk about the development of psychological crime fiction, so I did go away and find a copy and I read it, sitting the garden at midday in bright sunshine and I got some interesting things out of it. Fortunately I only got the one night of waking up in the small hours, wondering what that noise in the hall was and being unable to get out of bed to find out, because if I did the thing under the bed would grab my ankle. So I’m thankful for that.

All of this is why when I tell people that I write fantasy fiction and they say oh, but that’s just escapism, I’m always going to ask why they say that like it’s a bad thing. Because fantasy fiction, across the whole gamut from vampires and werewolves, through swords and sorcery, all the way to ray guns and rocketships is all about just this sort of positive escapism.

Whenever we’re reading a book, we’re stepping away from our own world to a place where we can see what we’ve left behind from new angles; where we can better appreciate complexities that ordinarily we’re too close to, or alternatively, where we can see a crucial simplicity within the bigger picture that we haven’t noticed before. We’re in a place where the normal rules don’t necessarily apply and that means we can look at those rules and maybe even test their validity. And with fantasy fiction, probably more than any other, we’re in a place where we can have fun doing this.

I reckon this is what winds these people up most, the people who want to dismiss the whole spectrum of speculative fiction. We can explore the intricacies of the human condition with wizards and dragons and dirty work at the crossroads. We can apply ourselves to the eternal verities with zombies and entrails if we want to. If we so choose, we can discuss philosophical, political and psychological development with green-skinned women on planets with four moons. We’re doing everything that the snobbiest literary critic demands of books and we’re having fun and they’re not. So I hope you’ve had fun at this convention because I most certainly have. Thank you.”

The J.R.R. Tolkien Lecture on Fantasy Literature 2024 – Speaker Neil Gaiman

Living in Oxfordshire, I’m fortunately able to attend most of these lectures in person. Heading into Oxford yesterday afternoon, I already knew this would be as good as any previous year. In the twenty or so years since my path first crossed Neil’s at a convention, I’ve heard him talk many times, and he will always have something new, different and fascinating to say. This was no exception – but I’m not going to attempt to summarise, as the video will soon be available, and believe me, you really don’t want to miss that.

(While you’re waiting do check out the videos of previous years’ speakers available at the Tolkien Lecture website. Varied, fascinating and thought-provoking.)

One thing Neil said prompted me to make a note. He quoted CS Lewis quoting JRR Tolkien: ‘The only people who decry escapism are jailers ‘.

That reminded me of something which I couldn’t quite remember, if you know what I mean… I’ve found it now, and it is very well worth the read – Sherwood Smith and Rachel Manija Brown on Who Gets to Escape

That article was particularly interesting for me, given the responses I was seeing at the time to my trilogy The Hadrumal Crisis, where who can and cannot escape various situations underpins a lot of the story. I discuss that here.

One other note. As I reached the venue, Oxford Town Hall, I was struck by the tremendous variation in the ages and appearances of those waiting patiently for the doors to open. Proof, if any were needed, that there’s no readily identifiable demographic for fantasy fans. This is possibly one reason why passers-by catching buses home from work were so bemused by the queue – which was very soon reaching well down St Aldates and past Christ Church’s Tom Tower. The town hall is a big space and it was packed!

Why Do We Write Retellings? A guest post from Shona Kinsella

I’ve been back and forth with myself, pondering the answer to this question. With so many new ideas just waiting to be worked on, why do we, as writers, return to old stories? Why do some stories hold such power over us that we retell and reimagine and reexplore them over and over, centuries after they were first told? Perhaps, in some cases, it’s because there are voices in those stories which have never truly been heard, whether that’s the women of Arthurian legend as in Juliet’s The Cleaving, or Snow White from the point of view of the stepmother, as in Cast Long Shadows by Cat Hellisen. In other cases, maybe it’s following clues through history and archaeology to shine new light on old tales, as with Stephen Lawhead’s King Raven Trilogy which places Robin Hood in Wales, in the aftermath of the Norman Conquest.

Ultimately, I can’t speak for those authors, or tell you why they revisited these tales (although I can definitely recommend that you read the books, each one of them is wonderful). All I can really tell you, is why this story called to me.

So, why then did I feel the pull of a Scottish myth so old that its origins are lost to time?

Like many fantasy readers, I have always loved myth and legend and folklore, especially from Scotland. I spent a lot of time outdoors as a child, often in semi-wild places rather than in cultivated gardens and parks. I clambered over rocks on loch sides and riverbanks, made dens in the roots of trees, hunted for tadpoles and dragonflies in marshy, undeveloped land near my home, felt the wind and the sun and the rain – always the rain – on my skin as I searched for signs of the fae. Even now, though I spend more time in my office than outside, I never fail to turn my face to the sun on the first warm days of spring, to find joy in the changing of the seasons and to point out these markers to my children as we walk to school.

It is perhaps unsurprising then, that I should have such love for a myth which touches upon the lives of the gods said to govern the seasons – The Cailleach, the lady of winter, who formed the highlands by striding through the land dropping boulders from her apron; Bride, queen of spring, who is celebrated at Imbolc at the beginning of February; Aengus, god of Summer, love and poetry. It is not a particularly well-known myth outside of the Scottish highlands and certain pagan groups dedicated to the worship of one or other of these deities, which is initially how I stumbled across it. As a pagan dedicated to the worship of Brighid (also spelled Brigid, Bride, Brigit) this myth has deeply personal resonances for me.

In the original myth, The Cailleach is jealous of Bride’s youth and beauty and so imprisons the younger goddess in her cave on Ben Nevis. Aengus dreams of Bride, falling in love with her, and he borrows three days from summer to put the Cailleach to sleep. He rescues Bride and they flee across the land, bringing spring in their wake. The Cailleach wakes and chases them, which is why we have a false spring, often followed by blustery weather in March and April.

As much as I loved this myth as a way of understanding and explaining the seasons, it never sat quite right with me. In other tales, Bride is not a meek princess who would weep and wait for a man to come and rescue her and the Cailleach is powerful and fierce – unlikely to be so jealous of another’s beauty that she would resort to such measures. In fact, in many versions of the Cailleach’s story, she is said to grow young and beautiful over the course of winter, only to age again during the summer.

I began to wonder what this story would look like if the two women were not placed in opposition to each other. I thought about what the myth I was familiar with told us, not about the gods themselves, but about the people who wrote it down. The Cailleach is jealous of another’s youth and beauty because we imagine aging beyond attractiveness to men as being the worst thing that can happen to a woman, but what if it’s not? Wouldn’t it be far worse to have your value and contribution constantly overlooked? Bride is meek and mild and obedient because those were virtues that were valued in a wife, but what if she was strong? What if she was determined to have power over her own life?

Was it possible to keep the exploration of the seasons and what they mean to people, while honouring the gods as I saw them? The Heart of Winter is my attempt to do just that. I’ll leave it up to the reader to decide whether or not I achieved my aim.

https://www.flametreepublishing.com/the-heart-of-winter-isbn-9781787588318.html

Scottish fantasy author Shona Kinsella is the author of The Heart of Winter, The Vessel of KalaDene series, dark Scottish fantasy novella Petra MacDonald and the Queen of the Fae, British Fantasy Award shortlisted industrial novella The Flame and the Flood, and non-fiction Outlander and the Real Jacobites: Scotland’s Fight for the Stuarts. Her short fiction can be found in various magazines and anthologies. She served as editor of the British Fantasy Society’s fiction publication, BFS Horizons for four years and is now the Chair of the British Fantasy Society.

Shona lives near the picturesque banks of Loch Lomond with her husband and three children. She enjoys reading, nature walks, and spending time with her family. When she is not writing, doing laundry, or wrangling children, she can usually be found with her nose in a book.

overhung by oak branches

Thinking about the lenses we use to view history

We went to the Earth Trust/Dig Ventures festival of discovery on Sunday. We listened to two talks by teams of young, enthusiastic archaeologists discussing the finds from digs around Wittenham Clumps. One was on everyday objects, and the other was on ancient animals. In between, we had a very nice lunch, strolled around the local landscape, and went to the pop-up museum where a small selection of the thousands of finds was on display.

I expect many of us have seen Roman tiles with cat and dog prints left when the clay was still wet. This is the first time I’ve seen a fox leave its mark.

Then there were the mystery objects, such as this. I always ask Husband what he thinks. After studying it for a few moments, he proposed a use that one of the archaeologists confirmed is their experts’ current best guess.

Apparently a feature of Bronze Age sites is ‘pots in pits’, and there’s much discussion about what deliberate deposits of selected items might mean. Rituals linked to ‘end of use’ are generally proposed, though it’s impossible to know whether these marked, for example, a death, the demolition of a dwelling, or moving away from an area. One such pit here is particularly interesting as the objects deposited are a well-used, smashed pot, broken loom weights and a 4 year old sheep. When swords and other weapons are deposited in water or pits, they are deliberately broken to put them beyond use. Is this a similar ritual involving objects associated with textile production? Sheep for meat were usually slaughtered by the end of their second year. Beyond that, they were primarily kept for wool. What does this tell us about spinning and weaving and those who did it? That these women and their skills were respected with such rituals? What does that tell us about these ancient people and their society? Maybe it wasn’t all mighty-thewed warlords defending helpless women and children?

Another speaker observed that ‘hillfort’ is increasingly considered a misnomer for enclosures ringed with ditches and banks, as modern archaeology increasingly indicates they weren’t built for defence, not primarily at least. People could retreat into them at need, but for most people, most of the time, these appear to be trading and gathering centres, possibly seats of power for tribal leaders. Where did the people come from to trade and meet? DNA work on burials on this site is still pending, but at least two skeletons have been interpreted by bone experts as likely of African heritage.

This got me thinking about where that term ‘hillfort’ had come from. Field archaeology pioneers from the 1850s onwards started surveying and excavating these landscapes. The British Empire was at war with someone or other through most decades of the 19th and first half of the 20th centuries. How much did that background noise of perpetual conflict influence these men to see such earthworks as military and defensive? What assumptions followed? You only build defences when there’s an enemy out there. Therefore anyone new must be an invader! But what if that initial assumption is wrong? The the whole framework collapses. Finds that have been interpreted to fit that world view should be reassessed. This is just one reason why I find current archaeology so fascinating.

Since one of my personal lenses for viewing history is its use in world-building for fantasy writers, it’s apt that the next creative writing article from my archive is on this very topic.

The Uses of History in Fantasy